1. The Oppenheims

Max Freiherr von Oppenheim (1860–1946), was born into an extremely wealthy Jewish banking family in Cologne. The private bank known as “Sal. [i.e. Salomon] Oppenheim jr. & Cie,” founded in 1789, had a continuous, unbroken existence until 2010, when, having survived even its Arisierung (Aryanization) under the Nazis, it finally succumbed to the world financial crisis and was taken over by the Deutsche Bank. Only a few years earlier, with some 3,100 employees, it had still ranked as one of the largest private banks in Europe, if not the largest.

The Oppenheims are first mentioned as silk merchants in Frankfurt in the sixteenth century. In 1740 a Salomon Oppenheim moved to Bonn, where the Oppenheims became court factors of the Elector Clement August. The founder of the modern bank of Sal. Oppenheim jr. & Cie was a younger Salomon (1772–1828) who transferred his business in 1798 to Cologne.

His sons, Simon (1803–1880) and Abraham (1804–1878), together with their mother Therese, who had taken over the management of the firm on her husband’s death, transformed it into “one of the earliest and most important examples of modern commercial and industrial capitalism in Germany.” Linked by marriage to other Jewish banking families—the Rothschilds, the Habers, the Foulds—the Oppenheims were involved in the financing of Germany’s first industrial firms: they promoted railroad construction, river transportation, and insurance companies, and they helped to finance the up-and-coming heavy industry of the Ruhr.1 By the 1870s they were the wealthiest family in Cologne and both Simon and Abraham had been ennobled in recognition of their contribution to the development of the national economies of Germany and Austria. When the German Empress happened to be in Cologne, she dined at the Oppenheims’; Abraham and his wife Charlotte were in turn guests of the royal couple when the latter stayed at the Residenzschloss in Koblenz.2

Fig. 1.1 Portrait of Salomon Oppenheim jr., founder of the Oppenheim bank. Artist unknown (before 1828). Wikimedia Commons (original in colour).

During most of the nineteenth century, members of the family identified themselves without hesitation as Jews, even if Benedict Fould on a visit to Cologne in 1813 wrote home to his father in Paris that Salomon Oppenheim jr. “n’est pas plus ami que toi des cérémonies juives.”3 Thus in 1841 Simon and Abraham submitted “a humble petition” for a more complete emancipation of the Jews to the King of Prussia. Their youngest brother David (1809–1889), a liberal who in 1842 launched the Rheinische Zeitung and brought Karl Marx in to edit it, also embraced the cause of Jewish emancipation and continued to support it even after he himself had converted to Catholicism in 1839 and taken the name Dagobert.4 In the mid-1850s Abraham donated 600,000 thalers (over a million and a half dollars in today’s money by some estimates) for the building of a new synagogue in Cologne, the land for which had been purchased by his father in the 1820s, while in his will (1880) Simon made provision for a home for old, infirm or indigent Jews.

Fig. 1.2 Synagogue in the Glockengasse, funded by the Oppenheim family, 1861. Lithograph by J. Hoegg from a water colour by Carl Emanuel Conrad (1810–1873). Wikimedia Commons (original in colour).

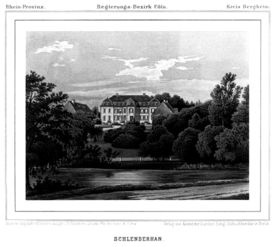

At the same time, however, the family also supported general philanthropic and cultural ventures in Cologne. They clearly wanted to be seen as good citizens whose Judaism did not prevent them from pursuing the wellbeing of all, Christians and Jews alike, in their community. Almost all the family’s numerous charitable bequests, beginning with one from Therese in 1829, stipulate that they are for the “needy of all faiths” or “without regard to religion.” The beneficiaries of this Oppenheim generosity ranged from the poor in general to victims of flooding and industrial accidents, starving workers, veterans of the War of Liberation (1812–1813), and officers wounded in the wars of 1866, 1870, and 1914–1918. Substantial sums were contributed to support scholarships at the University of Bonn for gifted boys from poor families, as well as to the Institute for the Deaf and Dumb and the city orphanage. On Abraham’s death in 1878, his widow Charlotte (1811–1887)—a granddaughter on her mother’s side of the great Mayer Amschel Rothschild—donated 600,000 marks (between two and a half and three million dollars in today’s money) to establish the Freiherr Abraham von Oppenheim’scher Kinderhospital, the first children’s hospital in Cologne (1880) and a few years later (1885) another 400,000 (100,000 for the building, plus an endowment of 300,000) for a new general hospital in nearby Bassenheim, where the family had acquired an estate. In the early twentieth century, Flossy (Florence Mathews Hutchins), the American wife of Simon Alfred von Oppenheim (1864–1932)—Simon’s grandson, who headed the bank in the first three decades of the twentieth century—continued the tradition by setting up a convalescent home in Schlenderhan, where the family had also acquired a handsome country house and built up a celebrated stud farm.

Cultural institutions were not neglected. Therese and her two sons Simon and Abraham were among the founding members of the Cologne Kunstverein [Art Association] in 1839 and members of the family were subsequently strong supporters of the city’s Wallraf-Richartz Museum, which opened its doors in 1861, donating funds for new acquisitions as well as pictures from their own collections. Dagobert was a particularly generous donor and benefactor, as well as a strong supporter of young artists of the Düsseldorf School. The Oppenheims were also among the first to support the Central-Dombau-Verein, set up in 1842 to finance and oversee the national project of completing Cologne’s great cathedral, and they contributed generously and consistently to it over the next thirty years. In recognition of their munificence, Abraham and Simon were made honorary committee members of the Verein in 1860. In 1864 Dagobert, along with some of his business associates, commissioned a stained glass window for the Cathedral representing—not an insignificant choice of subject—the conversion of St. Paul; while after Abraham’s death in 1878 his widow Charlotte donated another window in memory of her deceased husband. In 1859 Simon and his son Eduard (1831–1909) played a major role in the establishment of the Cologne Zoo and the “Flora” Horticultural Society. In 1863 a major gift from Abraham, providing a suitable endowment for the annual salary of an outstanding music director for the city, together with further gifts made directly to the institution itself, helped to turn the Cologne Conservatorium der Musik, originally founded in 1845 as Rheinische Musikschule,5 into one of the leading music schools in Germany. Further substantial donations from Oppenheim family members followed and in 1910 and 1912 a major expansion of the conservatory, presently the largest in Germany, was made possible thanks to significant gifts from Albert von Oppenheim (1834–1912) and his estate. The second son of Simon and the father of Max von Oppenheim, Albert von Oppenheim, served on the Cologne Conservatory’s governing board for fifty years, from 1860 until 1910, and as its president from 1898 until 1910.

Nor were the Oppenheims slow to demonstrate their loyalty through gifts to members of the royal and imperial households—on the silver anniversary of the “Kaiserpaar,” Prince William (the future Wilhelm I) and Princess Augusta (1854); on the wedding of Friedrich Wilhelm (the future Friedrich III, felled by cancer after a 99-day reign) and Princess Victoria of England (1855); on the golden wedding anniversary of the Kaiserpaar (1870)—and by contributing to monuments honouring the royal family, national heroes, and great moments in Germany’s history. In 1871 Simon’s son Eduard (1831–1909) contributed toward the construction of the Niederwald monument celebrating the re-establishment of German unity and the German Empire; in 1889 Dagobert gave 3,000 thalers for a monument to Kaiser Wilhelm I in Cologne; in 1897 the Bank contributed 6,000 thalers for a monument to the short-lived Kaiser Friedrich Wilhelm III; and in 1914 Simon Alfred made a large contribution to the proposed—never built—Bismarck National Monument on the Elisenhöhe at Bingerbrück.

In 1867, “for services in railway financing,” Simon was ennobled by Emperor Franz Josef of Austria with the hereditary title of baron (Freiherr); Abraham received the same honour from the Prussian monarch a year later. The family marked its entry into the higher ranks of German society by the purchase of notable landed properties. Schloss Bassenheim was acquired in 1873 (for over 540,000 thalers). At the Schlenderhan estate, purchased a year or two before, Simon’s son Eduard founded what soon became the leading horse stud farm (Gestüt) in Germany.

Fig. 1.3 Schloss Schlenderhan. Acquired by the Oppenheims in 1867. Lithograph by Thomas Hartmann, after an original by H. Deiters. Alexander Duncker, Die ländlichen Wohnsitze, Schlösser und Residenzen der Ritterschaftlichen Grundbesitzer in der Preussischen Monarchie, in naturgetreuen künstlerisch ausgeführten, farbigen Darstellungen nebst begleitendem Text (Berlin: Alexander Duncker, 1857–1883), vol. 9 (1866–1867), Plate 530 (original in colour).

Eduard and his son, Simon Alfred (1864–1932), were keen and accomplished horsemen and the Oppenheims were soon prominent in the elite Union-Klub, Berlin’s equivalent of the Paris Jockey Club, membership of which was drawn from the Prussian aristocracy, the landed gentry, and wealthy industrialists. The Klub seems to have been a significant entry point for extremely wealthy Jewish or part-Jewish families into the highest ranks of society.6 For many years Simon Alfred, head of the Oppenheim bank in the early decades of the twentieth century, was its President. “The turf was his world,” according to one history of the family and the bank, “Schlenderhan and horse-breeding a noble passion. […] He liked to be seen and to have his photograph taken, along with his regimental comrades, in his colourful uniform as captain in the elite cavalry regiment of the Zieten Hussars. Congratulatory messages were customarily exchanged with the family of the Crown Prince. Simon Alfred and his family felt at home in the uppermost ranks of German society, in the aristocracy, and on the racecourses of Europe.” Meantime at their home, the villa known as “Thürmchen” on Cologne’s Riehlerwall, in the years leading up to World War I, Simon Alfred’s American-born wife Flossy entertained prominent figures from the commercial, financial, and industrial worlds and aristocrats, high and low, from the ranks of the military, the diplomatic service, and the civil administration, along with family members from near and far.7

Max von Oppenheim himself grew up in a magnificent Louis XV-style town palais in the Glockengasse which his father, Albert, had acquired from his father-in-law, the Cologne patrician Philipp Engels, and next to which he had built an addition to house his outstanding collection of paintings. This collection, the core of which had been acquired in 1823 by Salomon Oppenheim jr.,8 included works by van Dyck, Frans Hals, Hobbema, Hans Holbein the Younger, Memling, Rembrandt, Rubens, Ruisdael, Jan Steen, David Teniers, and Velasquez.9

How the Oppenheims viewed their Jewish background or how their view of it may have evolved in the course of their rapid rise to prominence in the nineteenth century is hard to determine. On the window that Charlotte Oppenheim, Abraham’s widow, donated to Cologne Cathedral in memory of her deceased husband, the two lowest panes represent, on the left, the Oppenheim coat of arms and the family motto (Integrita, Concordia, Industria), and on the right, the family’s contributions to the civic life of Cologne. On this pane are represented not only the hospitals, the Horticultural Society, and the Cathedral, but also the new synagogue. Likewise in a frieze decorating a wall in the Cologne City Hall by the then well-known artist and lithographer Tony Avenarius (1836–1912) and depicting various benefactors of the city, Charlotte is shown with a model of the children’s hospital in front of her, while at her side Abraham is seen holding the deed of gift of the synagogue. The message of Charlotte’s stained glass window seems to be the family’s commitment to the entire community and of course, by the placement of a window bearing the family name and coat of arms in the Cathedral, its prominent place in that community.10 The Avenarius frieze is similarly ecumenical in spirit. Neither Abraham nor Simon followed the example of their younger brother David (or Dagobert) in embracing Christianity. Of Salomon Oppenheim jr.’s six daughters, five in fact still married Jews, mostly the sons of other bankers; only one, Eva, married a Christian, the Prussian Lieutenant-General Ferdinand von Kusserow. (Their son Heinrich was later to head the colonial affairs section of the Auswärtiges Amt, the German Foreign Office, and was to have a considerable influence, in this capacity, on Max von Oppenheim, who referred to him as his “uncle.”) Simon, however, the only one of Salomon’s three sons to have children, appears to have decided that in the interests of the family and the bank, his children, especially his two sons Eduard (1831–1909) and Albert (1834–1912), who were set to take over the business, should consolidate the integration of the family into German and Cologne society by taking Christian wives and themselves converting to Christianity.11 In 1856, Albert married Pauline Engels, the daughter of a prominent Cologne Catholic family and himself embraced the faith of his wife. The following year his brother Eduard also married a Cologne Christian heiress and converted to Protestantism. As Eduard and Albert were the only male heirs, the family’s and the firm’s Jewish connection was thereby ended, in principle at least. Max von Oppenheim was the son of Albert. He was baptised at birth and raised as a Roman Catholic. He himself tells that there was a private chapel in the handsome town house of his parents, where mass was regularly celebrated.12

Footnotes

1 For a short summary of Oppenheim activities, see Richard Tilly, “Sal. Oppenheim jr. & Cie,” in Manfred Pohl, ed., Handbook on the History of the European Banks (Aldershot: Edward Elgar, 1994), pp. 451–57; on Oppenheim participation in railway construction, see Kurt Grunwald, “Europe’s Railways and Jewish Enterprise: German Jews as Pioneers of Railway Promotion,” Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook, 12 (1967): 163–209. The main source of information remains the outstanding work of Michael Stürmer, Gabriele Teichmann and Wilhelm Treue, Wägen und Wagen. Sal. Oppenheim jr. & Cie. Geschichte einer Bank und einer Familie (Munich and Zurich: Piper, 1989).

2 Michael Stürmer, Gabriele Teichmann and Wilhelm Treue, Wägen und Wagen, p. 214.

3 “Is no fonder of Jewish rituals than you” Cit. François Barbier, “Banque, famille et société en Allemagne au XIXe siècle,” Revue de Synthèse, 114 (1993): 127–37 (p. 131).

4 David Oppenheim’s conversion, the first in the family, is noted by Wilhelm Treue in his article “Dagobert Oppenheim: Zeitungsherausgeber, Bankier und Unternehmer in der Zeit des Liberalismus und Neumerkantilismus,” Tradition: Zeitschrift für Firmengeschichte, 9 (1964): 145–75, and by Shulamit S. Magnus, Jewish Emancipation in a German City: Cologne 1798–1871 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), p. 275.

5 It was renamed Conservatorium der Musik in 1858.

6 According to Philipp, Fürst von Eulenburg, the influential favorite of Kaiser Wilhelm II, “jeder Mensch, der Rennpferde hält, ist nach dem Standpunkt des Unionklubs ein ‘hervorragender Gentleman.’ Ausserdem sind sehr reiche Juden (wie die Oppenheims) in der Lage, Geld zu ‘pumpen.’ Das ist ungefähr die moralische Basis des Klubs, der in ‘gesellschaftlichen’ Fragen und Fragen der ‘Ehre’—in dem ‘was sich schickt und nicht schickt,’—massgebend ist.” (From the typescript of a text by Eulenburg, cited in Philipp Eulenburgs Politische Korrespondenz, ed. John C.G. Röhl, 3 vols. [Boppard am Rhein: Harald Boldt, 1976–1983], vol. 3, p. 1916, note 7.) According to Friedrich von Holstein, head of the Political Department at the German Foreign Office in the 1890s, the “Fürstlichkeiten” (“princely types”) of the Union-Klub supported the efforts of the club’s Jewish members (Max von Oppenheim is explicitly named) to enter areas of government and administration hitherto virtually closed to Jews, such as the Diplomatic Service. (See letter from Holstein to Eulenburg 21 July 1896, in Philipp Eulenburgs Politische Korrespondenz, letter 1382, vol. 3, pp. 1916–17.)

7 Michael Stürmer, Gabriele Teichmann and Wilhelm Treue, Wägen und Wagen, pp. 315–16.

8 The Sammlung Siebel was acquired by Salomon Oppenheim jr. from Johann Gerhard Siebel (1784–1831), a well-to-do Elberfeld textile merchant, diplomat, writer, art-lover, and keen freemason, who had fallen into financial difficulties. The collection was widely known, having been publicly exhibited in the Düsseldorf gallery.

9 For information on the charitable and philanthropic activities of the Oppenheims in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and on Albert von Oppenheim’s remarkable art collection, I am indebted to Viola Effmert’s richly documented Sal. Oppenheim jr. & Cie. Kulturförderung im 19. Jahrhundert (Cologne, Weimar and Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 2006). See especially the tables at the end of the volume.

10 For a brief (but not particularly sympathetic) overview of the Oppenheim family’s engagement in all aspects of the life of the city of Cologne, from the early nineteenth century to the present day, see Ulrich Viehöver, Die EinflussReichen (Frankfurt and New York: Campus Verlag, 2006), pp. 240–43.

11 For a somewhat different view of the conversions of Eduard and Albert, largely based on speculations in Michael Stürmer, Gabriele Teichmann, Wilhelm Treue, Wägen und Wagen, pp. 206–12, see Morten Reitmayer, Bankiers im Kaiserreich. Sozialprofil und Habitus der deutschen Hochfinanz (Göttingen: Vandenhoek und Ruprecht, 1999). According to Reitmayer, the subordinate role in the Oppenheim bank business to which Simon and Abraham had been restricted as long as their mother Therese was still alive (they had held only a 10% share of the firm) led them in their turn to retain control and keep their own sons in a subordinate position. The marriages and conversions of Eduard and Albert are thus construed as acts of revolt resulting from the younger men’s resentment at their “crown prince” status (p. 245).

12 It is also noteworthy that Oppenheim’s sisters Klara and Wanda both married into Catholic families.