2. The Charm of the Orient

It was intended that, as the oldest of the male children of Eduard and Albert, Max (1860–1946) should enter the family firm and be trained to take it over when the time came. Max, however, was not at all interested in running the bank. He had developed a keen curiosity about the Islamic world and dreamed of devoting his life to the study of the peoples and cultures of the Middle East and North Africa.

Interest in the “Orient” was by no means uncommon at the time, as several excellent studies of Western fascination with the Middle East have amply demonstrated.1 For a time, as Ottoman expansion brought Islamic rule to the gates of Vienna and the Barbary Corsairs disrupted shipping and raided towns on the Mediterranean, the Muslim Middle East and North Africa were regarded with fear. Travellers did not go there freely and most Western reports of the area and its peoples came from men who had been captured by the Barbary pirates and then escaped. With the Enlightenment and the weakening of Ottoman power and influence came a growing fascination with Turkey and other “Oriental” lands, manifested in the paintings of Antoine de Favray and Jean-Etienne Liotard, for instance. On the one hand, in texts such as Montesquieu’s Lettres persanes and the anonymous, immensely popular L’Espion turc, the perspective of the “Oriental” was used as a device for carrying out an Enlightenment critique of Western customs and institutions. On the other hand, Turkey, Egypt, North Africa, and Arabia became an exotic destination for the curious and for adventurers of various sorts—personal, political, and commercial (Domingo Badia y Leblich a.k.a. Ali Bey al Abassi, Richard Pococke, James Silk Buckingham, and later, in the nineteenth century, Richard Burton and William Gifford Palgrave, to mention only a few). They also became the objects of a “scientific” interest in exploring and mapping a terra incognita. The Enlightenment project of “unveiling” and shedding the light of reason and understanding on everything obscure or mysterious inspired the celebrated journeys of exploration of the Dane Carsten Niebuhr, of the North German doctor Ulrich Jasper Seetzen, of the modest young man from Basel, Jean-Louis Burckhardt, of the Italian Giovanni Battista Belzoni, of the Finn Georg August Wallin, and of the Frenchmen Louis Linant de Bellefonds and Léon de Laborde, who had been preceded, of course, by the pioneering contributors to the celebrated Description de l’Egypte (1808–1829). The ambivalence of the relation of these travellers and explorers of the “Orient” toward the objects of their inquiry—at once sympathetic curiosity and condescending conviction of their own superiority, with more than a dash, in some cases, of imperialist acquisitiveness—is amply, if one-sidedly laid bare, at least as far as the English and the French are concerned, in Edward Said’s now virtually classic Orientalism.2 By the early nineteenth century the secrecy of the harem had been penetrated and “Oriental” women were being exhibited in full view, in various states of undress (so-called “odalisques”), in the canvasses of artists from colonising lands, such as France (Ingres, Delacroix, Gerôme and Chassériau). It would be hard to imagine a more direct demonstration of the triumph of the West. Naturally enough, Mecca, the holiest site of Islam, became a particularly enticing mystery to be unravelled and exposed to the inquiring Western eye.

By the close of the nineteenth century, interest in the Orient had become inseparable from the colonial ambitions and rivalries of the European powers. At the same time, the coming of the machine age and the high degree of self-discipline and self-consciousness, the constraints and artifices required and promoted by modern Western civilization, together with a sense of individual alienation amid the fraying of traditional communal bonds, led to a growing fascination with cultures which were seemingly unaffected by modernity and in which certain human qualities (whose disappearance from modern societies had already been noted with regret by Adam Smith’s compatriot Adam Ferguson in his Essay on the History of Civil Society [1767]) continued to shape people’s lives: heroism; honour; loyalty; the absolute law of hospitality to the stranger; proximity to the world of nature; being simultaneously a proudly independent agent and an inseparable part of a community, rather than an isolated individual in competition with other individuals in a liberal society that, in theory at least, recognized no distinctions among the units composing it. Above all, perhaps, the supposed stability of an unshaken and unquestioned traditional way of life appealed strongly to many in the West who observed with dismay the accelerating mutations of their own culture and society. “We live in an age of visible transition,” Bulwer-Lytton observed gloomily in 1833, “an age of disquietude and doubt—of the removal of time-worn landmarks, and the breaking up of the hereditary elements of society. Old opinions, feelings, ancestral customs and institutions are crumbling away, and both the spiritual and temporal worlds are darkened by the shadow of change.” In this context the unchanged and seemingly unchanging world of the East held a special attraction.

To Alexandre Dumas, writing four years later, the “strange and primitive world” of the desert, “the counterpart of which is found only in the Bible, […] seemed to have just come from the hand of God.”3 Oppenheim‘s contemporary and occasional correspondent, Alois Musil, the learned cousin of the great Austrian writer, relates in 1908 that he was drawn to study the tribes of Arabia Petraea because the conditions of life there closely resembled those of Biblical times.4 Oppenheim himself noted with admiration that “das Leben der Beduiner ist im wesentlichen heute nicht anders als es uns von den Dichtern und Geschichtsschreibern der altarabischen Zeit vorgeführt wird. Wie die Wüstensteppe seit Jahrtausenden dieselbe geblieben ist, so auch der Beduine […] von Europas Kultur noch unbeleckt” [“the life of the Bedouins is essentially no different today from what is presented to us in the works of the classical Arabic poets and historians. Just as the desert steppe has remained the same for thousands of years, so has the Bedouin remained unaffected by the culture of Europe”].5 The hero of John Buchan’s 1916 novel Greenmantle was expressing a common view when he told the mysterious and dangerous German agent Hilda von Einem that, in the decades before the outbreak of war in 1914,

the world, as I see it, had become too easy and cushioned. Men had forgotten their manhood in soft speech, and imagined that the rules of their smug civilisation were the laws of the universe. But that is not the teaching […] of life. We had forgotten the greater virtues, and we were becoming emasculated humbugs whose gods were our own weaknesses. Then came war, and the air was cleared. Germany, in spite of her blunders and her grossness, stood forth as the scourge of cant. She had the courage to cut through the bonds of humbug and to laugh at the fetishes of the herd. Therefore I am on Germany’s side. But I came here for another reason. I know nothing of the East, but as I read history it is from the desert that the purification comes. When mankind is smothered with shams and phrases and painted idols a wind blows out of the wild to cleanse and simplify life. The world needs space and fresh air. The civilisation we have boasted of is a toy-shop and a blind alley, and I hanker for the open country.

The hero characterizes his own words as “confounded nonsense” invented to trick his interlocutor. But only a few pages later, another of the novel’s heroes makes a very similar and—the reader is meant to believe—authentic claim to explain why he is deeply attracted to Islam. He rejects, as a decadent version of the true Orient, the voluptuous, feminized image of the “Orient” propagated by the art of Ingres, Delacroix, Gérôme, Chassériau, and a host of less well known painters, as well, in some measure, as by the writings of some widely read historians. In the work of Edgar Quinet and his friend Jules Michelet, for instance, the “Orient” was represented as the origin, the body, the female, the secret of whose infinite fecundity it is the task of the male to penetrate, transform into knowledge, and make subservient to “higher” intellectual and spiritual ends. The true Orient, however, Buchan’s character maintains, is, on the contrary, austere and masculine—not the fetid swamp of Michelet or of the Swiss scholar and investigator of “oriental” matriarchy, J.J. Bachofen, but the arid, bone-dry desert, the home of the fearless and restless Bedouin:

The West knows nothing of the true Oriental. It pictures him as lapped in colour and idleness and luxury and gorgeous dreams. But it is all wrong. The Kâf he yearns for is an austere thing. It is the austerity of the East that is its beauty and its terror … It always wants the same things at the back of its head. The Turk and the Arab came out of big spaces, and they have the desire of them in their bones. They settle down and stagnate, and by the by they degenerate into that appalling subtlety which is their ruling passion gone crooked. And then comes a new revelation and a great simplifying. They want to live face to face with God without a screen of ritual and images and priestcraft. They want to prune life of its foolish fringes and get back to the noble bareness of the desert. Remember, it is always the empty desert and the empty sky that cast their spell over them—these, and the hot, strong, antiseptic sunlight which burns up all rot and decay … it isn’t inhuman. It’s the humanity of one part of the human race. […] There are times when it grips me so hard that I’m inclined to forswear the gods of my fathers!6

As is well known, a good number of Westerners did forswear the gods of their fathers, and openly or secretly converted to Islam. Others—Jean-Louis Burckhardt, even Kaiser Wilhelm II—were rumoured to have converted.

Fascination with a society seemingly still free of the constraints of “civilization” and still governed by a shared traditional code of behaviour underlies the admiration for the Bedouins that Max von Oppenheim shared with many of his predecessors and contemporaries—albeit not, to be sure, with all travellers to the Near and Middle East.7 Even the sober Dane, Carsten Niebuhr, noted with admiration that the Bedouins are “passionately fond of liberty.”8 Jean-Louis Burckhardt, not given to exaggeration of any kind, but still susceptible to Enlightenment and early Romantic ideals, found the Bedouins, in comparison with the European peoples, “with all their faults, one of the noblest nations with which I ever had an opportunity of becoming acquainted.” Jean-Louis seems to have viewed them as a kind of Swiss (or Scottish Highlanders) of the desert, free of the corrupting influence of courts and cities. Compared to “their neighbours the Turks, […] the Bedouins appear to still greater advantage,” the young Swiss wrote in his plain and lucid English.

The influence of slavery and of freedom upon manners cannot any where be more strongly exemplified than in the characters of these two nations. The Bedouin, certainly, is accused of rapacity and avarice, but his virtues are such as to make ample amends for his failings; while the Turk, with the same bad qualities as the Bedouin, (although he sometimes wants the courage to give them vent,) scarcely possesses any one good quality. Whoever prefers the disorderly state of Bedouin freedom to the apathy of Turkish despotism, must allow that it is better to be an uncivilised Arab of the Desert, endowed with rude virtues, than a comparatively polished slave like the Turk, with less fierce vices, but few, if any, virtues. The complete independence that the Bedouins enjoy has enabled them to sustain a national character. Whenever that independence was lost by them, or at least endangered by their connexion with towns and cultivated districts, the Bedouin character has suffered a considerable diminution of energy, and the national laws are no longer strictly observed.9

To later nineteenth- and early twentieth-century travellers also, such as Lady Jane Digby, Richard Burton, Lady Anne Blunt, and finally T.E. Lawrence (“Lawrence of Arabia”) the people of the desert, unlike the urban Arabs, seemed unspoiled by civilization—though these admirers appear to have thought of them less in terms of the “noble savage” of the Enlightenment or Burckhardt’s free and democratic Swiss mountain people, than, in more conservative vein, as aristocrats of the spirit, a kind of “natural gentlemen,” the polar opposite of the undifferentiated masses created in Europe by urbanization, industry, and democratic politics.10 Oppenheim himself used the English term when he noted that “Angeboren ist dem Beduinen eine gewisse Vornehmheit des Benehmens. […] Jeder Einzelne benimmt sich wie ein Gentleman, wenn er, der altarabischen Verpflichtung zur Gastfreundlichkeit folgend, in seinem Zelt einen Gast empfängt”11 [“A certain aristocratic demeanor is natural to the Bedouin. […] Every individual behaves like a gentleman when, in accordance with the age-old Arab obligation to offer hospitality, he receives a guest in his tent.”]

It could be that, in Oppenheim’s case, admiration of the Bedouins, along perhaps with interest in the Middle East in general, was not unconnected with insecurity about his own place in a society that both admitted him to its ruling elite and, as we shall see, excluded him from it on account of his part-Jewish background. As a traveller in the Middle East and in Africa, and subsequently as an agent of the Auswärtiges Amt, he unflaggingly promoted Germany’s political and economic interests in the Islamic world. “Wenn ich auf irgend eine Weise deutsch-patriotischen Interessen förderlich sein könnte,” he wrote to his early mentor, the Africa explorer Gerhard Rohlfs, “so würde dies zu erreichen mein heissestes Bestreben sein”12 [“If I could promote Germany’s national interests in any way, it would be my most fervent wish to do so.”] His enthusiasm for the Bedouins may well have been in some measure at least, another expression of his determination to be and be seen as undivided in his identification with and loyalty to Germany, for his Bedouins are portrayed in the first volume of his monumental four-volume study of them (1939–1946)—the volume to which his contribution, as distinct from that of his collaborators Erich Bräunlich and Werner Caskel, was greatest—with traits that recall both the ideal German of extreme conservative circles in the Wilhelminian era and, in 1939, the ideal German of the National Socialists. They are, we are told, pure, fearless, unspoiled by “civilization”: “ein Herrenvolk, urwüchsig, primitiv, wild und kriegerisch” [“a master race, unspoiled, rooted, fierce, and warlike”]. In addition, the Bedouin is described in terms all too familiar to the German reader of 1939 as “unendlich stolz auf die Reinheit seiner Abstammung, die er hütet und pflegt. Nur die Beduinen sind für ihn aşīl (reinblütig). Tief eingewurzelt ist ihm der Glaube an die verbindende und verpflichtende Macht des Blutes” [“infinitely proud of the purity of his descent, which he watches over and is careful to preserve. Only Bedouins are aşīl [of pure blood] in his eyes. Belief in the binding and commanding power of blood is deeply rooted in him”]. Not perhaps without some bearing on the author’s own situation as the son of an “Aryan” and patrician German mother, emphasis is also placed on the important role in their racial make-up that the Bedouins attribute to the mother: “High value is placed on purity of descent not only on the father’s side but on that of the mother too. Moreover, it is not only racial purity that counts. Attention is also paid to nobility of descent. Even the greatest warriors of ancient Arabia […] suffered on account of a mother’s descent from a tribe held in low esteem, or even a black woman. To this very day the pure-blooded Bedouin (aşīl) does not take a wife from any tribe deemed not of pure blood or not of noble blood.”13 In the eyes of one of Oppenheim’s younger friends and associates, the Breslau Professor of Oriental Philology and translator of the Gilgamesh (1911) Arthur Ungnad, there was indeed such a remarkable similarity of the pure Semite to the pure German that he was prepared, in 1923, to entertain the hypothesis of their having been originally one Volk:14

Racially pure Semites, such as may still be found among the Bedouins of the Arabian Desert differ physically only very slightly from people of the Indo-Germanic race, to which we ourselves belong and to which, these days, the misleading name Aryan is given. Stick one of those sons of the desert into the oilskin of a gaunt weather-tanned Nordic fisherman and cover the latter with the picturesque mantle of the Bedouin; the most knowledgeable person will not be able to tell easily which of the two is the Semite and which the European. There are likewise striking linguistic connections between the Semitic and Indo-Germanic races. Everything suggests that the hypotheses, according to which the original homeland of the Semites was Arabia or even Africa, do not hold up. It is far more likely that in distant times, long before any historical records, both peoples formed part of a single people with a single language, probably located in South-Eastern or Central Europe.15

In this heroic, aristocratic, and racially pure society of the Bedouins, Oppenheim relates with satisfaction, he was recognized as a German baron and accepted as an equal and a friend. In his writings Oppenheim constantly emphasized the affection, respect, candor, and trust that characterized his relationships with the Bedouins. Unlike many previous travellers, he noted for instance, he did not attempt, by donning a disguise and assuming a Muslim identity, to pass himself off as a Muslim and win acceptance under a false pretense.16 Deceit and concealment had no place in his relations with the peoples of the region, he insisted; he was known to and respected by his Arab friends as a German aristocrat. Hence the pride and pleasure with which he described, in 1900, how, before witnesses, he was ceremoniously made a “brother” of Faris Pasha, the chief of the Shammari Bedouins, the tribe he most admired.17 “In Northern Arabia, Syria, and Mesopotamia I often lived with the Bedouins, those free sons of the desert, sharing their tents with them,” he recounted later, recalling his sojourns in the Middle East both before and during his years of service as attaché at the German Consulate-General in Cairo. “I had a very good understanding of their soul, their language, and their mores. I had grown fond of these people and they welcomed me everywhere with open arms.”18

Was there somewhere in Oppeneim’s account of his relations with the Bedouins a discreet or even unconscious reproach to his own society for treating him as not quite one of theirs? Though in his eagerness not to raise the issue of his Jewish ancestry, he avoided referring to anti-Semitism even in private documents, Oppenheim had to have known it was anti-Semitism that was preventing him from being considered fit for the higher levels of the Imperial diplomatic service and from being fully part of the social group to which he did not doubt that he belonged. Could it be that in presenting a Semitic people in a noble, dignified, even heroic light, not only in his writing but in the many photographs he took of groups and individuals, and in showing how he, as a German, was fully accepted into the select ranks of a tribe highly conscious of its members’ genealogies, Oppenheim was creating an inverted mirror-image of his own situation in Wilhelminian Germany?

For him, as for others, the tribal communities of the “free sons of the desert” offered a striking contrast to the modern West—and not only, perhaps, to the fraying of traditional social bonds often attributed to the influence of the Jews, but to a vulgar and undiscriminating modern anti-Semitism that failed to distinguish between noble and base.

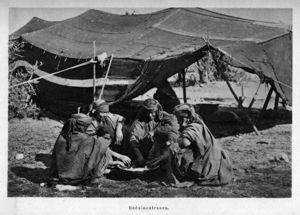

Fig. 2.1 “Bedouin Women.” Photograph from Oppenheim’s Vom Mittelmeer zum Persischen Golf (1899). Dr. Max Freiherr von Oppenheim, Vom Mittelmeer zum Persischen Golf durch den Haurān, die Syrische Wüste und Mesopotamien (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer, 1899), vol. 2, facing p. 124.

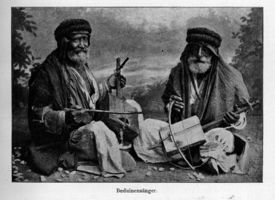

Fig. 2.2 “Bedouin Minstrels.” Photograph from Oppenheim’s Vom Mittelmeer zum Persischen Golf. Ibid., vol. 2, p. 127.

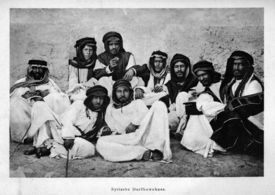

Fig. 2.3 “Syrian Villagers.” Photograph from Oppenheim’s Vom Mittelmeer zum Persischen Golf. Ibid., vol. 1, facing p. 254.

It has in fact been noted that a disproportionate number of full Jews were drawn to “Oriental” studies in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, some even converting to Islam; and it has been speculated that this interest in Islam, while facilitated in many cases by the scholars’ knowledge of a Semitic language and familiarity with non-Christian religious ideas and practices, may well have been a response to Christian anti-Semitism.19 At the same time it seems also to have been motivated both by rejection of the Talmudic spirit of modern Orthodox Judaism, especially as it had evolved among the Jews of Eastern Europe, and by revulsion at the materialist, commercial culture that, in the eyes of some Jewish orientalists no less than in those of Christian anti-Semites, had come to characterize their contemporary Western fellow-Jews.20 Disraeli’s popular novel Tancred—published in German translation in the same year (1847) as it appeared in English—turns modern anti-Semitism on its head by claiming that “It is Arabia alone that can regenerate the world” and that between the early Jews and the Arabs there is no essential difference. The former are Mosaic Arabs and the latter Mohammedan Arabs.” “The Arabs are only Jews upon horseback,” as Disraeli neatly put it. Jew and Arab alike belong to the same Bedouin race, which, moreover, in contrast to the modern European peoples, is pure and unmixed.21 One of the early successes of a contemporary of Oppenheim’s, the poet Börries, Freiherr von Münchhausen (a descendant of the celebrated eighteenth-century Baron of the same name), who was subsequently a thoroughly anti-Semitic supporter of the National Socialists, was a volume of poems in praise of the heroic Jews of yore. Münchhausen’s Juda. Gesänge (Goslar, 1900) was praised by Herzl as a call to modern Jews to return to the heroic virtues of their ancestors and, as such, comparable with Byron’s appeal to the modern Greeks.22 But it is by no means unlikely that Münchhausen himself intended his work to be understood by his readers as a call to modern Germans to return to the heroic way of life of their pure Nordic ancestors. Enthusiasm for the “free sons of the desert,” in sum, could function as a critique of anti-Semitism that was itself not incompatible with certain strains in contemporary anti-Semitism.

It remains true that in many accounts of travels in modern Muslim lands, Muslims and Jews are presented as mutually opposed and hostile. Thus in The Travels of Ali Bey in Morocco, Tripoli, Cyprus, Egypt, Arabia, Syria, and Turkey (London, 1816), Domingo Badia y Leblich described—not, in his case, without compassion and indignation—the contempt in which the Jews of Morocco were held by the Muslim population and the exclusions and humiliations to which they were subject.23 And in general, Westerners who were drawn to the Arabs and to Islam because of their primitive virtues tended to see Jews from the angle of nineteenth-century anti-Semitism, that is, as rootless and devious harbingers of a destabilizing modernity. Richard Burton, for instance, the author of the hugely popular Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Medinah and Meccah (1855–1856), refrained from publishing The Jew, The Gypsy and El Islam—in which his account of the Jews is said to be partly based on his experiences as British Consul in Damascus (1869–1871)—after “an influential friend who was highly placed in the official world advised against it” for as long as Burton remained in government service, “owing to the anti-Semitic tendency of the book” and thus the risk of giving offence to the “powerful Jews of England.” The editor of the posthumously published 1898 edition, W.H. Wilkins, omitted an Appendix on alleged “Human Sacrifice among the Sephardim”—a rehash by Burton of the so-called “Damascus Affair” of 1840 in which, in a revival of ancient blood libel charges, several distinguished members of the Jewish community of Damascus had been accused and convicted of having abducted and murdered a Catholic priest. Wilkins conceded, however, that even without the defamatory appendix the tone of the book was “anti-Semitic,” as indeed the section on the Jews assuredly is, in comparison with the favourable presentation of the Gypsies and, especially, of “El Islam.”24

Following a suggestion of Arthur Ungnad, who had come under the influence of the race researcher Hans F. K. Günther (known as “race-Günther”),25 Oppenheim himself came to consider the Jews a mixed race, composed partly of invading Semites and partly of the Subaraean people among whom they allegedly settled. The Bedouins, whom he so admired, he considered, in contrast, “pure Semites.”26 The Bedouins thus represented for him what the ancient Jews had represented for Münchhausen, and there could thus no longer be any question of praise of the Bedouins’ serving as a disguised critique of popular anti-Semitism.

Oppenheim’s attitude to the Jewish element in his background is a topic to which we shall have to return in the section of our study devoted to his situation, as a “Mischling” (i.e. not a pure “Aryan”) under National Socialism. For the moment, we can at least safely affirm that, at a time when Germany was vigorously pursuing a close political, military, economic, and cultural association with the Ottoman Empire—to such an extent that both the official and unofficial German responses to the massacres of Armenian Christians in the mid-1890s, in contrast to the outraged popular and official responses in most European countries, were strikingly restrained27—Oppenheim’s warm relations with the Muslim Near East were in themselves fully consonant with his German patriotism. An emergent new Turkey was widely seen as the creation of German advisers in economics and finance, in the military, in engineering, and even in culture, prompting a close associate of Oppenheim’s in his later wartime activities to exclaim, after ushering a group of Ottoman dignitaries around Germany: “That’s what the Turks are like? So cultivated and clever, so imposing and simpatico, so European, ja – so German!”28 At one of the high points of German-Turkish relations, Sultan Abdul Hamid II himself noted “une certaine analogie de caractère entre nous et les Allemands”—in contrast to the French, who, he claims, are closer to the Greeks—“et c’est là sans doute,” he added, “une des raisons qui nous attirent vers eux.”29 On his side, as is well known, Kaiser Wilhelm II professed profound sympathy with the world’s Muslims and in a famous speech at the tomb of Saladin in 1898 declared himself their protector.

In 1883, after Max had obtained a law degree, Albert von Oppenheim permitted his son to undertake a journey to the “Orient,” having apparently reconciled himself to the fact that his brother Eduard’s son, Simon Alfred (1864–1932), would most probably take over the direction of the bank instead of Max. Thus in the winter of 1883–1884 Max von Oppenheim, aged 23, got to accompany his “uncle,” Heinrich von Kusserow (the son of Salomon Oppenheim jr.’s daughter Eva and the Prussian Lieutenant-General Ferdinand von Kusserow), a strong advocate in German government circles of an aggressive colonial policy, to Athens, Smyrna, and Constantinople. In 1886 he spent six months in Morocco on what he describes as a Forschungsreise [research trip], and he learned Arabic. He himself outlines the subsequent development of his career until 1909 in the first volume (1939) of his book on the Bedouins. It is obvious even from this brief narrative—on which we shall expand somewhat in the following chapters—that Oppenheim’s activity as a scholar and his activity as an agent of the German government were always closely conjoined:

In 1892 I was able to begin pursuing my scholarly activities in the Orient on a larger scale. With the ethnographer Wilhelm Joest, a fellow-citizen of Cologne, I travelled from Morocco right across North Africa. At the end of the trip I stopped for seven months in Cairo, where I lodged in an Arab house in the native quarter. Here I lived exactly as the local Muslims did in order to develop my fluency in the Arabic language and to study thoroughly the spirit of Islam and the customs and manners of the native inhabitants. My plan was to prepare myself in this way for further expeditions that would lead me into the Eastern part of the Arab world.

In the spring of 1893, my path led me to Damascus. From here I set out on my first truly major research trip in the Near East. It is narrated in my two-volume book Vom Mittelmeer zum Persischen Golf durch den Haurān und die Syrische Wüste [1899–1900].

On matters concerning the Bedouins, I could count, throughout the expedition, on a very good adviser, namely Manșūr Nașr, a nephew of Sheikh Midjwel el Meșrab […] the husband of Lady Digby, the beautiful Englishwoman, who has become celebrated because of her unusual career. After an adventurous life at various European courts, she was on a journey from Damascus to Palmyra in the year 1853, when she fell in love with and married Sheikh Midjwel. To him, in contrast to her earlier European husbands and lovers, she remained faithful. She spent six months out of every year sharing the life of the desert with him, until she died, in August 1881, in her house in Damascus.

As early as this 1893 trip I was able to collect much material on the Bedouins. […] In the course of this expedition I came to love the wild, unconstrained life of the sons of the desert. […] In Cairo I had already become accustomed to eating with my fingers (one may use only those of the right hand), as was still then the practice in the Cairene middle classes, instead of with a knife and fork. On the 1892 expedition, that had naturally been how I ate with the Bedouins, both when I was their guest and when they were my guests. By sharing their way of life in the saddle and in the tent, I acquired ever greater knowledge of their ways. They felt that I was well disposed toward them and that I understood their customs and peculiarities. Hence, they were also well disposed toward me and readily answered any question I put to them. […]

The return journey from Mesopotamia took me by way of the Persian Gulf and India to our then young and beautiful colony of East Africa. I made an expedition into the interior, in the course of which I acquired an extensive piece of land in Usambara. This was later turned into plantations [in footnote: “by the Rheinische Handel-Plantagen-Gesellschaft,30 which here successfully cultivated first the coffee bean, and then, after the coffee worm made its appearance, sisal—until this flourishing plantation was lost to Germany as a consequence of the World War.”] […]

From there I returned to Cairo, where in early 1894 I met Zuber Pasha who, by hunting for men to sell as slaves, had succeeded in establishing a large principality. As he began to become too strong, however, Khedive Ismail [the ruler of Egypt, nominally subject to the Ottoman Sultan in Constantinople] enticed him to Cairo where he detained him in a beautiful palace, which was like a gilded cage. From Zuber Pasha, I obtained extraordinarily interesting information about one of his former generals named Rabeh, who had refused to capitulate to the Egyptians and had moved westwards from the Nile valley with a large number of his former soldiers and their families.

Back in Germany, I wrote up a report on this, as well as on other things I had learned in Cairo about the area around Lake Chad and about the Muslim order of the Senussi, which was of great importance not only from a religious but also from a political standpoint. This report led the Auswärtiges Amt to ask me, in the context of our rivalry with France and England, to lead a German expedition into the hinterland of the Cameroons in order to acquire the area up to Lake Chad for Germany. […]

Our expedition plans had to be abandoned, however. In the competition involving France, England, and Germany the aforementioned Rabeh had moved faster than the European powers. Starting out from the Egyptian Sudan he had led his army from victory to victory, like a black Napoleon, and had seized all the lands south of Wadai [a former kingdom situated between Lake Chad and Darfur] together with the large kingdoms of Bagirmi and Bornu. Nevertheless, his reign was of short duration. He fell in a battle with the French and the empire he founded collapsed. When his lands were divided up by the European colonial powers, my expedition, which was all set to go, became part of the bargaining process. Germany received the so-called “Caprivi-strip” of our Cameroons colony, namely large parts of Bagirmi and Bornu and thereby access to Lake Chad.

From then on I was employed by the Auswärtiges Amt and attached to our diplomatic legation in Cairo. From there I was in a position to observe closely all the affairs of the Islamic world. No place was better for this than Cairo. The Egyptian Press, published in the Arabic of the Koran,31 was of decisive importance for the entire Islamic world from the Atlantic to China. Whereas in Turkey Sultan Abdul Hamid wielded absolute power and did not tolerate the free expression of opinion in the newspapers, Cairo was the resort of all Muslim political refugees, especially those from the Ottoman Empire itself.

But I also managed to establish excellent relations with Sultan Abdul Hamid [… who] asked me to call on him whenever I was in Constantinople, which I regularly did.32

By his own characteristically self-promoting account, in short, Oppenheim succeeded in building connections with many different factions and interests in the Muslim world, including both the Sultan and those in the Ottoman Empire who opposed him. He was thus, the reader was to infer, in an excellent position to gather intelligence on behalf of the Auswärtiges Amt. He goes on in this retrospective on his career to tell of the “excellent relations” he established through the Sultan with the family of Emir Faisal, who was to become King of Iraq; with Abdul Huda, the Sultan’s close adviser and the head of the “widespread Muslim brotherhood of Rifa’ija”; and with many other personalities of the Muslim world, such as one Mohammed Ibn Bessam, from whom he learned a great deal about “the development of power relations in central Arabia in the last [i.e. nineteenth] century and down to the First World War.” Perhaps Oppenheim hoped to emulate Emin Pasha—the Jewish-born convert Eduard Schnitzer, who had become a national hero in Germany on account of his efforts to develop and promote German power and influence in Africa.

With a few interruptions for short missions to Washington and Paris, Oppenheim spent the years from 1896 until 1909, he relates, in Cairo, where his house “was on the border between the native and the European quarters.” The lavish style in which he entertained his guests here, it may be added, was soon the talk of Cairo. Crown Prince Wilhelm of Germany, Duke Carl-Eduard of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (a cousin of George V of England and subsequently an Obergruppenführer in the Nazi SA), Princess Radziwill, John Jacob Astor, and Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt were among the prominent figures in European and American society, along with many leading Egyptians and other Muslim notables, who enjoyed his hospitality.33 Even the British, who, as we shall see, distrusted him deeply, conceded shortly before he left Cairo in 1909 that he was “one of the most popular of Cairo’s hosts.” In the words of the English-language Egyptian Gazette, “It is impossible to describe the charm of the baron’s house by comparison, since no comparison exists.”34 Oppenheim’s glamorous reputation may well have been enhanced by his habit of taking “temporary wives,” of whom apparently there were many. One, to whom he was particularly attached, came to a sad end. In a Cairo bazaar in 1908, it is said, he had the audacity to approach a married Arab woman. As he described her in the memoir he wrote toward the end of his life, she was “very pretty, very young” and made her way to the steam baths with a “swinging, elastic gait,” hidden behind a veil and guarded by a muscular eunuch. Oppenheim’s relationship with her ended in catastrophe when her husband discovered their affair and killed her.35

Footnotes

1 E.g. Sari J. Nasir, The Arabs and the English (London: Longman, 1976); Peter Brent, Far Arabia. Explorers of the Myth (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1977); James C. Simmons, Passionate Pilgrims. English Travellers in the World of the Desert Arabs (New York: William Morrow, 1987); the magnificently illustrated book of Alberto Siliotti, Egypt Lost and Found. Explorers and Travellers on the Nile (London: Thames and Hudson, 1998), and, of course, the (for good reason) controversial study of the late Edward Said, Orientalism (New York: Pantheon, 1978). One of the earliest such studies was the aptly titled and still richly informative The Penetration of Arabia by the Oxford scholar and teacher of “Lawrence of Arabia,” David George Hogarth (London: Lawrence and Bullen, 1904).

2 Though he attempts to explain it, Said’s decision to exclude Germans, Danes, and Italians from consideration is a serious flaw in his book. It may also have led him to mistake Jean-Louis Burckhardt for his relative, the great historian Jacob Burckhardt (p. 160). Both were members of the same prominent, super-rich Basel family, but belonged to different branches and generations. Jean-Louis’s family and its business had suffered severely as a result of the Napoleonic wars and the young Jean-Louis was forced to try to make a living in England. His travels in the Middle East were undertaken on behalf of the Society for the Exploration of the Interior Parts of Africa, which hoped to discover the source of the river Niger by having its agent Burckhardt join a party of Africans returning from the Hajd.

3 Lytton and Dumas quoted in James C. Simmons, Passionate Pilgrims. English Travellers in the World of the Desert Arabs, pp. 94–99. The Austrian writer Hermynia Zur Mühlen (1883–1951), who spent much time in her youth in North Africa and the Middle East with her diplomat father before she renounced her aristocratic background and became a Communist, had a more ambivalent response: on the one hand the Orient represented, for her too, sunlight, clarity, spontaneity and exuberance, in contrast to the darkness, meanness, and hypocrisy of the European world; on the other hand it was also marked by violence and age-old superstitions and fanaticisms; see her memoir, Ende und Anfang (Berlin: S. Fischer, 1929), pp. 94–95 et passim (Engl. trans. The End and the Beginning [Cambridge: Open Book Publishers, 2010], available at: https://doi.org/10.11647/obp.00015).

4 Alois Musil, Arabia Petraea (Vienna: Alfred Hölder, 1908), vol. 3 (“Ethnologische Reisebericht”), Vorwort, p. v. Musil later published an important 700-page scholarly study of the Bedouins, The Manners and Customs of the Rwala Bedouins (New York: American Geographical Society and Czech Academy of Sciences and Arts, 1928).

5 Max Freiherr von Oppenheim, with the collaboration of Erich Bräunlich and Werner Caskel, Die Beduinen (Leipzig: Otto Harrassowitz, 1939), vol. 1, p. 26. See also Gabriele Teichmann, “Grenzgänger zwischen Orient und Okzident. Max von Oppenheim 1860–1946,” in Gabriele Teichmann and Gisela Völger, eds., Faszination Orient. Max von Oppenheim—Forscher, Sammler, Diplomat (Cologne: DuMont, 2001), p. 52: “Was Max von Oppenheim seeking—assuredly not only that—a bright world of harmony and beauty? In his homeland, at any rate, society had been thrust into a historically unprecedented transformation by the industrial revolution which had brought mass migrations of labour, the disappearance of traditions, technical progress that provoked both wonder and anxiety, a fraying of the bonds of religion, and challenges to the old elites from political parties and trades unions—in short a spirit of fundamental change and unrest. In the Orient, in contrast, Oppenheim could imagine himself in a world in which age-old models were still being followed and history seemed, as it were, to have stood still.” At least on this point, Oppenheim and Johann Heinrich Count Bernstorff, who was German Consul-General in Cairo during part of Oppenheim’s appointment as special attaché there and who did not appreciate Oppenheim’s provocations of the British or the memos sent over his head to Berlin, were in agreement. “The Orient seems eternally unchanged,” Bernstorff wrote in his memoirs, “in spite of the efforts and activities of native and foreign governments. […] All innovations do but touch the surface.” (Memoirs of Count Bernstorff, trans. Eric Sutton [New York: Random House, 1936], p. 34.)

6 John Buchan, Greenmantle, ed. Kate Macdonald (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1993; 1st edn 1916), pp. 179, 182–83.

7 The half-Jewish Jesuit, William Gifford Palgrave, broke early on with the prevailing admiration for the Bedouins. Relatively rare among the travellers of his day, he far preferred “the Arabs of inhabited lands and organized governments” to the “nomades of this desert.” Though “these populations are identical in blood and tongue,” the difference between them is comparable to that “between a barbarous Highlander and an English gentleman.” (Personal Narrative of a Year’s Journey through Central and Eastern Arabia (1862–63), 5th edn [London: Macmillan, 1869; 1st edn 1865], p. 17.) Half a century later, similar views were expressed by Oppenheim’s contemporary, the Oriental scholar Martin Hartmann, a champion of progress, modernisation, and free thought and of the efforts of some Muslims to embrace these. In a letter to his friend, the eminent Hungarian Orientalist Ignaz Goldziher, Hartmann poured scorn on the University of Groningen Professor Tjitze de Boer’s History of Philosophy in Islam (London: Luzac and Co., 1903), now something of a classic: “The opening is shockingly naïve: ‘In older time (how old? 1000 years ago? 3000 years ago?), the Arabian desert (unknown to me, except for the Nefud…!) was the roaming-ground of independent (really? mostly this ‘independence’ looked pretty wretched) Bedouin tribes. With free and healthy minds,’ etc.!!! These dirty disease-ridden scoundrels were of free and sound mind!!—i.e. they would sell themselves to anyone for a few pennies and were so ‘healthy’ that they devoured each other, when they could, over any stranger who came their way. This kind of naivety, nurtured by our drawing-room Arabists, who know nothing of the real world, should no longer be found today in the work of a serious writer.” (Martin Hartmann to I. Goldziher, 12 April 1904, in “Machen Sie doch unseren Islam nicht gar zu schlecht.” Der Briefwechsel der Islamwissenschaftler Ignaz Goldziher und Martin Hartmann 1894–1914, ed. Ludmila Hanisch [Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2000], pp. 210–11.)

8 Travels through Arabia and other Countries in the East, trans. Robert Heron, 2 vols. (Edinburgh: G. Mudie, 1792), vol. 2, p. 172.

9 John Lewis Burckhardt, Notes on the Bedouins and Wahabys, published by authority of the Association for Discovering the Interior of Africa, 2 vols. (London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1831), vol. 1, p. 358.

10 See Lady Ann Blunt, Bedouin Tribes of the Euphrates, ed. W[ilfrid]. S[cawen]. B[lunt], (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1879) and A Pilgrimage to Najd, the Cradle of the Arab Race, 2 vols. (London: John Murray, 1881), esp. vol. 1, pp. 408–17. See also, in note 21 below, Benjamin Disraeli on the desert Arabs and the original desert Jews as “an aristocracy of Nature.” William Gifford Palgrave appears to have been exceptional in far preferring the urban Arabs to those of the desert.

11 Dr. Max Freiherr von Oppenheim, “Bericht über seine Reise durch die Syrische Wüste nach Mosul.” Offprint from Verhandlungen der Gesellschaft für Erdkunde zu Berlin, 1894, no. 4 (Berlin: Druck von W. Pormetter, 1894), 18 pp. (p. 15).

12 Cit. Wilhelm Treue, “Max Freiherr von Oppenheim. Der Archäologe und die Politik,” Historische Zeitschrift, 209 (1969): 37–74 (p. 45). Cf. Gabriele Teichmann, “Fremder wider Willen—Max von Oppenheim in der wilhelminischen Epoche,” in Eckart Conze, Ulrich Schlie, Harald Seubert, eds., Geschichte zwischen Wissenschaft und Politik: Festschrift für Michael Stürmer zum 65. Geburtstag (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2003), pp. 231–48: “Dem aus jenem Krieg [against France, 1870–1971] hervorgegangenen Kaiserreich zu dienen, dessen Macht zu mehren, war eines der bestimmenden Lebensthemen Max von Oppenheims, das er in verschiedenen Variationen spielte—als Orientforscher und Archäologe, als Diplomat und Propagandist” (p. 231). On chang1es in German interest in the Near and Far East in the new circumstances of the Second German Empire, see Suzanne Marchand, German Orientalism in the Age of Empire (Washington, D.C.: German Historical Institute and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), pp. 212–27, 333–67 et passim.

13 Die Beduinen, vol. 1, pp. 26, 27. Oppenheim probably knew of the determining role Jewish tradition attributes to the mother in the definition of a Jew. By Jewish standards, he was not Jewish at all, not simply because he had been baptised, but because his mother was a Catholic.

14 The modern reader may be surprised to learn that this was by no means an outlandish position at the time. A lively debate pitted scholars who argued that the Indo-Germanic and Semitic language families were related and had a common origin against those, like Ernest Renan, who rejected that view. Renan, however, argued in favor of the “unité primitive” of the Indo-Germanic and Semitic “races,” notwithstanding that the two languages were, in his opinion, completely distinct. “La race sémitique et la race indo-européenne, examinées au point de vue de la physiologie, ne montrent aucune différence essentielle; elles possèdent en commun et à elles seules le souverain caractère de la beauté. […] Il n’y a donc aucune raison pour établir, au point de vue de la physiologie, entre les Sémites et les Indo-Européens une distinction de l’ordre de celle qu’on établit entre les Caucasiens, les Mongols et les Nègres. […] L’étude des langues, des littératures et des religions devait seule amener à reconnaitre ici une distinction que l’étude du corps ne révélait pas. Sous le rapport des aptitudes intellectuelles et des instincts moraux, la différence des deux races est sans doute beaucoup plus tranchée que sous le rapport de la ressemblance physique. Cependant, même à cet égard, on ne peut s’empêcher de ranger les Sémites et les Ariens dans une même catégorie. Quand les peuples sémitiques sont arrivés à se constituer en société régulière, ils se sont rapprochés des peuples indo-européens. Tour à tour les Juifs, les Syriens, les Arabes sont entrés dans l’oeuvre de la civilisation générale, […] ce qu’on ne peut dire ni de la race nègre, ni de la race tartare, ni même de la race chinoise, qui s’est créé une civilisation à part. Envisagés par le côté physique, les Sémites et les Ariens ne font qu’une seule race […]; envisagés par le côté intellectuel, ils ne font qu’une seule famille” (Histoire générale et système comparé des langues sémitiques, 3rd edn (Paris: Michel Levy frères, 1863 [1st edn 1855], pp. 490–91). For a good summary of the varying positions in the debate, see Friedrich Delitzsch, Studien über Indogermanisch-Semitische Wurzelverwandtschaft (Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs, 1873), pp. 3–29. Delitzsch, who believed there is a case for a common origin of the two languages and was severely criticized on that account by Renan, criticises in turn Renan’s position (a single original race but two original languages) as contradictory (pp. 17–20). Ungnad was clearly on the side of Delitzsch in the debate.

15 Arthur Ungnad, Die ältesten Völkerwanderungen Vorderasiens: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte und Kultur der Semiten, Arier, Hethiter und Subaräer (Breslau: Im Selbstverlag des Verfassers, 1923), pp. 4–5. Under the influence of the race theories of Hans F.K. Günther who announced that “There is no such thing as a ‘Semitic race,’ there are only Semitic language-speaking peoples, constituted by varying racial combinations” (Rassekunde Europas [Munich: J. F. Lehmann, 1929], p. 100), Ungnad subsequently rejected the idea that there was such a thing as a “pure Semite” or a Semitic “race.” “Language is one thing, race another, and ‘Semitic’ describes a language family, not a race,” he declared in Subartu: Beiträge zur Kulturgeschichte und Völkerkunde Vorderasiens (Berlin and Leipzig: Walter de Gruyter, 1936): “Semitisch ist eine Sprache und keine Rasse” (p. 3).

16 Oppenheim, Die Beduinen, vol. 1, pp. 3–4.

17 Max Freiherr von Oppenheim, Vom Mittelmeer zum Persischen Golf durch den Haurān, die Syrische Wüste und Mesopotamien, 2 vols. (Berlin: Dietrich Reimer, 1899–1900), vol. 2, pp. 65–66.

18 Max von Oppenheim, “Reisen zum Tell Halaf,” (1931) in Gabriele Teichmann and Gisela Völger, eds., Faszination Orient, pp. 176–203 (p. 177).

19 See Martin Kramer, “Introduction,” in The Jewish Discovery of Islam: Studies in Honor of Bernard Lewis, ed. Martin Kramer (Tel Aviv: Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies, 1999), pp. 1–48; also Bernard Lewis, “The Pro-Islamic Jews,” in his Islam in History: Ideas, Men, and Events in the Middle East (New York: Library Press, 1973), pp. 123–37. Lewis points to the popularity of a simplified story according to which “the Jews had flourished in Muslim Spain, had been driven from Christian Spain, and had found a refuge in Moslem Turkey,” and argues that the Romantic “cult of Spain,” the contrast between a persecuting society in medieval Europe and a peaceable kingdom in Islamic Iberia, was a “myth” that had been “invented by Jews in nineteenth-century Europe as a reproach to Christians.” See also Susannah Heschel, Abraham Geiger and the Jewish Jesus (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), p. 61.

20 On rejection of Orthodoxy by Jewish scholars of Islam such as Abraham Geiger (1810–1874), Heinrich Graetz (1817–1891), and Ignaz Goldziher (1850–1921), the Hungarian Jew who was one of the founders of the modern historical study of Islam, see John M. Efron, “Orientalism and the Jewish Historical Gaze,” in Ivan Davidson Kalmar and Derek J. Penslar, eds., Orientalism and the Jews (Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 2005), pp. 80–93. Goldziher Islam was purer and less burdened by remnants of idolatry and superstition than Judaism and Christianity, he sympathized with its struggle against “the dominant European plague,” and considered working with the nouveaux-riches Jews on the executive board of the Israelite Congregation of Pest, of which he had been appointed Secretary after failing to obtain a university appointment, an “enslavement” (Raphael Patai, Ignaz Goldziher and his Oriental Diary: A Translation and Psychological Portrait [Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1987], pp. 27–29). On Aby Warburg’s association of the wealthy Hamburg Jews with an ostentatious and materialist culture, see Ron Chernow, The Warburgs (New York: Random House, 1993), pp. 121–22.

21 Benjamin Disraeli, Tancred (London and Edinburgh: R. Brimley Johnson, 1904), p. 299. In Coningsby (1844) Disraeli had traced the ancestry of the character of Sidonia, whom many readers associated with a member of the Rothschild banking family, to the reconverted “New Christians” of Spain and behind them to the Jews of Arabia. “Sidonia and his brethren could claim a distinction which the Saxon and the Greek and most of the Caucasian nations have forfeited. The Hebrew is an unmixed race. Doubtless among the tribes who inhabit the bosom of the Desert, progenitors alike of the Mosaic and the Mohammedan Arabs, blood may be found as pure as that of the descendants of the Scheik Abraham. But the Mosaic Arabs are the most ancient, if not the only, unmixed blood that dwells in cities” and “an ummixed race […] are the aristocracy of Nature.” (Coningsby [Teddington, Middlesex: The Echo Library, 2007], p. 159; see Minna Rozen’s essay on Disraeli in Martin Kramer, ed., The Jewish Discovery of Islam, pp. 49–75; and Georg Brandes, Lord Beaconsfield: a study [New York: Charles Scribner’s, 1880], pp. 42–43.)

22 See L. Gossman, “Jugendstil in Firestone: The Jewish Illustrator E.M. Lilien (1874–1925),” Princeton University Library Chronicle, 66 (2004): 11–78 (pp. 33–40).

23 The Travels of Ali Bey in Morocco, Tripoli, Cyprus, Egypt, Arabia, Syria, and Turkey, 2 vols. (London: Longman, Hurst, Orme and Brown, 1816), vol. 1, pp. 33–35; see also the extensive documentation in Bat Ye’Or, The Dhimmi: Jews and Christians under Islam (Rutherford, Madison, Teaneck: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1985; [orig. French edn, Paris: Editions Anthropos, 1980]), especially pp. 291–385.

24 Richard F. Burton, The Jew, The Gypsy and El Islam, ed. W. H. Wilkins (Chicago and New York: Herbert S. Stone & Co., 1898), pp. vii–x.

25 According to Günther, “a series of false ideas has been spread about the Jews. Thus they are supposed to belong to a Semitic race. But there is no such race. There are only peoples of varying racial composition speaking Semitic languages. The Jews themselves are supposed to constitute a ‘Jewish race.’ That is also false. The most superficial observation discovers people looking quite different from each other among the Jews. The Jews are supposed to constitute a single religious community. That is equally a most superficial error. For there are Jews of all the major European faiths and even among those most committed to a völkisch idea of the Jew, i.e. the Zionists, there are many who do not subscribe to Mosaic doctrines. […] The Jews are a people, and, like other peoples, they belong to different confessions, and, like other peoples, they are an amalgam of different races…” (Rassenkunde Europas, 3rd edn [Munich: J. F. Lehmann, 1929; 1st edn 1926], pp. 100–04).

26 M. von Oppenheim, Tell Halaf: Eine neue Kultur im ältesten Mesopotamien (Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1931), pp. 44–45.

27 See especially Vahakn N. Dadrian, German Responsibiity in the Armenian Genocide: A Review of the Historical Evidence of German Complicity (Watertown, MA: Blue Crain Books, 1996), pp. 8–15, and Margaret Lavinia Anderson, “‘Down in Turkey, far away’: Human Rights, the Armenian Massacres, and Orientalism in Wilhelmine Germany,” Journal of Modern History, 79 (2007): 80–111.

28 Ernst Jäckh, “Der Gentleman des Orients,” Reclams Universum, 29, no. 7 (1912), cit. Margaret Lavinia Anderson, “’Down in Turkey, far away,” Journal of Modern History, 79 (2007), pp. 97, 108. On an alleged “affinity between the Germanic and Islamic mind,” see Hichem Djaït, Europe and Islam, trans. Peter Heinegg (Berkeley/Los Angeles/London: University of California Press, 1985), pp. 78–79 et passim.

29 Ali Merad, ed., L’Empire Ottoman et l’Europe, d’après les “Pensées et souvenirs” du Sultan Abdul-Hamid II (Paris: Editions Publisud, 2007). This volume consists of 143 pp. of introduction and notes and a reprint (222 pp. separately numbered) of the original text of Abdul Hamid’s memoirs—Avant la Débâcle de la Turquie. Pensées et souvenirs de l’ex-Sultan Abdul-Hamid, recueillis par Ali Yahbi Bey (Paris and Neuchâtel: Attinger Frères, 1914). These “reflections and recollections,” dating from different periods of his reign, were supposedly communicated by the Sultan to his close friends around 1909, during the time of his banishment by the Young Turks to Salonika. The passage cited is on pp. 207–08 of the 2007 reprint of the 1914 text. The text was later translated into Turkish as Siyasi Hatiratim (Istanbul, 1974) and Arabic (Beirut, 1977).

30 Immediately on his return from Africa, Oppenheim had contacted his cousin Simon Alfred and some other Cologne entrepreneurs about exploiting the East Africa territory commercially. This led in 1895, in line with earlier colonial investments by the Oppenheim Bank, to the founding of the Rheinische Handel-Plantagen-Gesellschaft. For Oppenheim, patriotism and business, like patriotism and scholarship, went hand in hand (see below, Pt. 1, Ch. 6). The property, which made Oppenheim “Herr eines Fürstentums […], das grösser war als Reuss ältere und jüngere Linie zusammengenommen” [“lord of a principality (…) larger than Reuss—that of the older and that of the younger line together”], was acquired from the native tribal chief Kipanga for a bottle of schnapps and some 700 marks (Gabriele Teichmann, “Fremder wider Willen,” in Eckart Conze, Ulrich Schlie, Harald Seubert, eds., Geschichte zwischen Wissenschaft und Politik, p. 233; also idem, “Grenzgänger zwischen Orient und Okzident,” in Faszination Orient, p. 24).

31 In contrast to the Turkish press in Constantinople, which was not only printed in Turkish but more subject to censorship by the Ottoman authorities.

32 Oppenheim, Die Beduinen, vol. 1, pp. 3–6.

33 Gabriele Teichmann, “Grenzgänger zwischen Orient und Okzident. Max von Oppenheim 1860–1946,” in Faszination Orient, p. 45.

34 Egyptian Gazette, 13 April 1909, cit. ibid., endnote 86, p. 102. On his leaving Cairo in 1910, the Gazette again wrote (18 October 1910): “His departure from Egypt will be a great loss to the German Agency. […] His beautiful house was a byword for hospitality and its doors were always open to every savant that passed through Cairo.”

35 See http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/0,1518,741928,00.html.