8. Financial Difficulties. The Fate of the Tell Halaf Finds

On his return from Syria in the late fall of 1913, Oppenheim approached the Royal Museums in Berlin about donating the share of the finds at Tell Halaf that, with great difficulty, he had persuaded the Ottoman authorities to permit him to ship back to Germany—43 boxes containing the smaller orthostats and some fragments, along with plaster casts of those items that could not be removed. In return, he asked that the Royal Museums contribute 275,000 marks (around one and a half million dollars in today’s money) toward the expenses of packing, shipping, insurance, and restoration; that he have some say in how the items were displayed; and that space be made available for ongoing work associated with the finds. No agreement was reached, however. The Near Eastern collection, then housed in cramped quarters in the basement of the Kaiser Friedrich Museum, could not accommodate more artefacts; in addition, the Royal Museums were, or claimed to be, strapped financially. Then, in 1914, war broke out.

In 1926, with the opening of the new Pergamon Museum, in which the Near Eastern collection was assigned the main floor of the south wing, another opportunity presented itself. But again only a selection of the smaller orthostats and fragments actually found a place in the museum. In 1927, after Germany had joined the League of Nations, and again in 1929, Oppenheim was able to return to Syria, now a French mandate, to resume work at Tell Halaf and at the same time negotiate a distribution of the sculptures and other finds from the 1911–1913 excavations with the new authorities there. For what was to remain in Syria he helped to set up a special museum in Aleppo (the National Museum, founded in 1931), for which he provided plaster casts of the sculptures he had now been authorized to ship back to Germany.

Fig. 8.1 Façade of Aleppo National Museum, showing plaster casts of statuary shipped to Berlin by Max von Oppenheim. Wikimedia Commons.

For these latter items, the Near Eastern section of the State Museums no longer being an option, he accepted an offer by the Technical University of Berlin to place at his disposal, at no cost to him, a disused machine factory in the Charlottenburg district of the city. Despite inflation and economic depression, which ate into his fortune, Oppenheim succeeded in turning the old factory into a makeshift museum, the central feature of which was a reconstruction, from both original parts and plaster casts, of the grand entrance to the Temple Palace with its monumental statues. The opening ceremony took place on Oppenheim’s 70th birthday, 15 July 1930, in the presence of the original excavation team and a large number of scholars. A couple of weeks later it was opened to the general public from 10 am until 3 pm daily and from 10 am until 2 pm on Sundays, with no admission charge.

The Tell Halaf Museum immediately drew worldwide attention and was visited by archaeologists from every corner of the globe. The veteran Australian-born archaeologist V. Gordon Childe hailed it as “one of the most original and instructive museums in Europe.”1 The Baedeker Guide to Berlin soon awarded it a star. On 25 October 1930 the mass circulation weekly Illustrated London News carried a long article on it, based on a text by Oppenheim himself.

Fig. 8.2 Illustrated London News, October 25, 1930, front page, showing caryatids from Tell Halaf in newly opened Tell Halaf Museum.

The striking front cover of this issue was entirely taken up by the towering caryatids forming the entrance to the so-called Temple Palace as reconstituted at the Museum; the inside pages were also profusely illustrated. On 1 November 1930, there was a follow-up article, while a further article on 16 May 1931, also largely by Oppenheim himself, was devoted to the monumental figures he had discovered at Jebelet el-Beda, about forty-five miles from Tell Halaf. Harry Graf Kessler tells of attending a lecture Oppenheim gave on his finds in the Berlin Singakademie in October 1930. The hall, he notes, was “full to overflowing.”2 Well timed to coincide with the opening of the Museum, Brockhaus of Leipzig brought out the substantial, handsomely illustrated monograph Der Tell Halaf. Eine neue Kultur im ältesten Mesopotamien in 1931. This in turn was quickly translated into English, published in London and New York, and, as we saw, widely and, on the whole favourably reviewed.3 A beautifully illustrated article by Oppenheim himself summarizing the finds at Tell Halaf appeared in French in the scholarly journal Syria in 1932 and was published separately as a pamphlet a year later.4 A full French translation of the 1931 German text, revised, updated, and even more beautifully illustrated, was brought out by Payot in Paris in 1939.

The publication of the 1931 book and of its 1933 English translation elicited three substantial review-articles, embellished by illustrations, in the New York Times. These were not scholarly pieces (their authors were Gabriele Reuter, a successful German novelist who had begun to write reviews for the New York Times in the late 1920s, Louise Maunsell Field, a popular American novelist and critic, and Raymond R. Camp, who mostly wrote about hunting). Unlike the specialists, they did not question Oppenheim’s chronology or even indicate, except for Field, that it had been subject to serious question. On the contrary, the reviewers highlighted Oppenheim’s dramatic account of the discovery of the site, the sensational conclusions to be drawn from his dating of the statuary and reliefs, and his claims for a Subaraean civilization older than and on a par with the Sumerian and Egyptian civilizations. The development of the sphinx sculptures at Tell Halaf, in particular, elicited comment. Thus, according to Camp, Oppenheim had shown that “the great Sphinx of Egypt […] is probably the ultimate result of the motif established by the fourth stage of the sphinx at Tell Halaf,” while Field drew special attention to “Oppenheim’s interesting theory concerning this puzzling conception. It is his belief that the sphinx originated not in Egypt but in Subartu and was developed from the characteristic figure of a goddess standing on a lioness.”5

Finally—and surprisingly, in view of Oppenheim’s part-Jewish background and distinctly Jewish-sounding name—the first, sumptuously produced quarto volume of a scholarly inventory and study of the Tell Halaf finds, to which many specialists contributed, was published with countless high quality illustrations in wartime Berlin (1943) with Oppenheim named as the principal author. Three further volumes appeared after the War (and after Oppenheim’s death), between 1950 and 1962. In 2010 a short additional volume was devoted to the painstaking restoration of the sculptures, which had been shattered when the museum created to display them was hit by an incendiary bomb during an allied raid on Berlin in late Sepember 1943. At the Tell Halaf site itself excavation continues to this day resulting in an ongoing production of scholarly studies. A website is now devoted to this continuing work of research: www.grabung-halaf.de.

Oppenheim’s fortune had been depleted both by the enormous expense of the Tell Halaf excavations6 and by the economic situation in Germany in the aftermath of World War I. His financial situation was further eroded by the banking crisis of 1931, which affected the Oppenheims as well as virtually all German banks. Nevertheless, concurrently with the Museum, he set up a library and a foundation, the Max Freiherr von Oppenheim Stiftung or Orient-Forschungs-Institut, for promoting the study of the ancient and modern Middle East and continuing research—after the death of Oppenheim himself—in the area of Tell Halaf in particular.7

Among other things, the Stiftung turned out a short, well designed, and well illustrated guide to the new museum, with a 23-page introduction in which Oppenheim’s interpretation of the finds and of the “Subaraean culture” they allegedly represented was clearly and succinctly outlined. In order to finance these projects, however, Oppenheim not only had to cut back somewhat on his lavish living style, he had to take out substantial loans. Thus, on the strength of his limited partnership in the Oppenheim bank, he borrowed 250,000 Reichsmarks from the Otto Wolff trading company in Cologne, which, since 1923, he had been advising on its business with Turkey.8 But that sum was evidently not enough to ensure funding for the Museum and the Foundation, for he now began to think of selling some of his finds from Tell Halaf.

It appears to have been with that possibility in mind that he travelled to the United States in the late spring of 1931. On 9 May 1931, a little more than a week after his arrival, the New York Times interviewed him at his hotel in New York, the elegant Ambassador on Park Avenue at 51st Street (torn down in 1966), and carried a report headlined “German to Study Ancient Finds Here. Baron von Oppenheim, Berlin Archaeologist Wants to See Treasures from Ur. He Excavated Tell Halaf. Tells of Huge Stone Carvings 5,000 years old and of Civilization in 4,000 B.C.” It is clear from the Times article that Oppenheim still held to his chronology of the finds at Tell Halaf: “Although the excavations at […] Ur have been rich in treasures of gold and small objects of art, Baron von Oppenheim said, the finds at Tell Halaf have been richer in stone carvings, some of great size, 5,000 years old or more.” Oppenheim told the Times that he “intended to study the Near Eastern exhibits at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and at museums in Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston and other cities.” He appears also to have been in contact with the University Museums of Yale, Columbia, Princeton, and Harvard and to have given talks at those institutions. By his own account, “I came to the United States to study the remains of Babylonian art in American museums, especially the results of the excavations made in Ur, Bismaja, and Kish. I came also to discuss my discoveries with American authorities before putting the final touches on my Tell Halaf publication, which has just been issued (in German) by F.A. Brockhaus, Leipzig.” He returned to the U.S. in the fall of 1931 “in response to several invitations extended to me last summer to lecture on my findings at the Tell Halaf at some of your museums.” This time, he told Myron Bement Smith (1897–1970), an archaeologist, architect, and art historian who had been appointed Secretary of the newly created American Institute for Persian Art and Archaeology (later known as the Asia Institute) in New York City, that his “stay in the United States will extend to May 1932.” He was therefore “most willing,” as he put it to Smith, to respond to additional lecture invitations and promised that “the address would naturally be in English” (which his correspondence demonstrates he knew quite well) and would be “enlivened by beautiful lantern slides and a short moving picture illustrating the Tell Halaf Museum in Berlin.”9

It seems likely, however, that in addition to drumming up interest in Tell Halaf and in the forthcoming English translation of his book Oppenheim was also, perhaps mainly, interested in the sale of selected items from his collection—or even, it has been suggested, of the collection as a whole10—for he had brought samples to show to potential purchasers. Unfortunately, his timing was not good, for the U.S. was sinking ever deeper into the Great Depression. It does not appear that any deals were made. Nevertheless, Oppenheim did not give up the idea of selling off some of his finds to raise money for the support of the Museum and the Stiftung. In anticipation of better times to come, he left his samples in the Hahn Brothers’ fireproof warehouse on East 55th Street in New York: “I did not let myself be downcast by my failure to make sales,” he noted later in an autobiographical sketch.11 The eight orthostats ultimately found a new home, after 1945, at the Metropolitan Museum in New York and at the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore.

Fig. 8.3 Tell Halaf. Orthostat. “Seated Figure holding a lotus flower.” New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1943 (43.135.1) Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. All Rights Reserved.

Fig. 8.4 Tell Halaf. Orthostat. “Lion-hunt scene.” New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1943 (43.135.4) Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. All Rights Reserved.

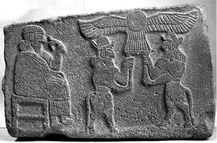

Fig. 8.5 Tell Halaf. Orthostat. “Two heroes pinning down a bearded foe.” The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Accession no. 21.18. Photo © The Walters Art Museum. All Rights Reserved.

Fig. 8.6 Tell Halaf. Orthostat. “Winged goddess.” The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore. Accession no. 21.16. Photo © The Walters Art Museum. All Rights Reserved.

In the meantime, Oppenheim’s only recourse was to borrow more money using his Tell Halaf finds as security. A list drawn up in 1943 identified forty objects that had served as collateral for such loans. This led on one occasion to a dramatic confrontation. One of Oppenheim’s creditors was a Dutch branch of the private, Berlin-based von der Heydt bank. Eduard von der Heydt, whose business associates included the Ruhr industrialists Stinnes and Thyssen and who was also the financial trustee and friend of the exiled Hohenzollerns, had written into the loan contract dawn up with Oppenheim in 1931 that, should Oppenheim not pay off his debt by 1934, the bank had the right to immediate seizure of the collateral. When this situation materialized, Eduard von der Heydt demanded that the items in question in the Tell Halaf Museum be immediately surrendered to him. He apparently intended to have them shipped to Ascona in Switzerland, where, in 1926, he had purchased the celebrated Monte Verità property, and where he intended that they should enhance his already world-renowned collection of Asian art. Oppenheim refused to yield his treasures and this led to an altercation of which we shall have more to say at a later point. Fortunately, Oppenheim was bailed out financially by a consortium of family members and friends. (Among the latter was his boyhood friend and old Cairo associate Hermann von Hatzfeld, whose father, Count Paul von Hatzfeld, had done what he could, many years before, to combat the prejudice against Oppenheim in the Auswärtiges Amt.)12

Oppenheim’s struggle to ensure the preservation and protection of his finds continued throughout the decade and into the War years. In 1935 he again entered into negotiations with the Near Eastern Section of the State Museums. But no agreement could be reached on price. Oppenheim based his estimate of the value of his finds on figures—in the millions—obtained at the end of the 1920s. The Museum authorities, citing among other things the allegedly uncertain legal status of the finds, claimed that these figures were now obsolete and proposed instead sums ranging between 460,000 and 475,000 Reichsmarks—sums that Oppenheim indignantly rejected. (His debts at this time ran to over a million, owed to several banks, among them his family’s bank, as well as to the consortium that had bailed him out in 1934 and to his cousin Simon Alfred von Oppenheim personally.) The authorities were in no hurry to compromise. It was in their interest to play a waiting game. As there were no competing offers, they figured, “the other side will gradually be worn down… The collection cannot escape us. If we only wait, the price will necessarily come down.” Realistically and cynically it was noted that Oppenheim, who was making the negotiations over price difficult, was almost eighty years old. In the end, Oppenheim failed to persuade the Museum to take over and house the finds from Tell Halaf. It took air raids on Berlin, as a result of which he was bombed out of his residence on the Savigny-Platz, with serious damage to some of the artefacts stored there as well as to the research library, to get the authorities to intervene and help him arrange for the most valuable books and Orientalia to be removed and stored in various castles and country houses around Berlin. And it was not until September 1943, when the Tell Halaf Museum itself received a devastating direct hit from an incendiary bomb, that its invaluable treasures, now in smithereens, were gathered up and finally removed to the relative safety of the bombproof vaults of the Pergamon Museum.13

Footnotes

1 Man, 34 (May 1934), p. 78.

2 Harry Graf Kessler, Das Tagebuch, ed. Günther Riederer and Jörg Schuster, 9 vols. (Stuttgart: Cotta, 2004–2010), vol. 9 (13 October 1930), p. 385.

3 Decades later, however, one notable scholar, the highly regarded Egyptologist Henri Frankfort, who was head of the Warburg Institute in London in the late 1940s and early 1950s, was to refer to it as “that boastful account, full of misleading statements and comparisons” (Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 11 [1952], p. 225).

4 “Tell Halaf, la plus ancienne capitale soubaréenne de Mésopotamie,” Syria, 13 (1932): 243–56; published separately by P. Geuthner, Paris, 1933.

5 Raymond R. Camp, “Origins of Mysterious Sphinx now Traced by Archaeology,” New York Times, 31 January 1932; Louise Mansell Field, “Kings who Ruled in Mesopotamia. Baron Max von Oppenheim’s ‘Tell Halaf’ is a Story of Adventure and Discovery in the Ruins of Subaraic Culture,”New York Times, 27 August 1933. Gabriele Reuter’s review, “A German Record of Ancient Life” appeared in the New York Times, 13 March 1932.

6 Recently estimated at the equivalent of 7–8 million euros (see http://www.tell-halafprojekt.de/de/max_von_oppenheim/oppenheim.htm).

7 “The Tell Halaf Museum is administered by the ‘Max von Oppenheim Foundation (Middle East Research Institute)’ established by Baron von Oppenheim at 6 Savigny Platz, Berlin. The Foundation’s field of research is the ancient and modern Middle East. Baron von Oppenheim has had the permits to carry out excavations at the sites of Tell Halaf, Fakhariya-Washukani und Djebelet el Beda, which were awarded him by the French Mandate authorities in Syria, registered in the name of his foundation. In this way he has ensured that the work of excavation, which will take many more years, can continue after his death.” (Führer durch das Tell Halaf-Museum, Berlin, Franklinstr. 6 [Max Freiherr von Oppenheim Stiftung, 1934], p. 26).

8 Teichmann, Faszination Orient, pp. 79–80.

9 Letter to Myron Bement Smith, dated “The Ambassador, New York, November 20th 1931.” Myron Bement Smith papers, the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Myron Bement Smith helped Oppenheim prepare a hand-out folder describing the lecture, which was entitled “The Wonders of Tell Halaf—A Hitherto Unknown Near-Eastern Culture of 5,000 Years Ago, described by its excavator, Dr. Baron Max von Oppenheim, Former German Minister Plenipotentiary.” In an earlier letter, sent from the Ambassador hotel on 11 November, Oppenheim had explicitly sought Smith’s “assistance in arranging a number of lectures that I intend to hold on my Tell Halaf.” He also submitted the texts of the hand-out and of his lecture to Smith so that the latter could check the English for him (letters of 24 November and 10 December). Smith and Oppenheim remained in contact for several years after that and Smith and his wife were entertained by Oppenheim in Berlin and given a tour of the Tell Halaf Museum in May 1933. In a letter to Ernst Herzfeld, written after the War, Oppenheim recalls having been invited to Princeton and having given a lecture there on Tell Halaf (letter dated 21 June 1946, Herzfeld papers, the Freer Gallery of Art and the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. B-16; see Appendix for text of this letter).

10 Nadja Cholidis and Lutz Martin, Der Tell Halaf und sein Ausgräber Max Freiherr von Oppenheim, p. 50. In support of this claim, the authors cite a letter of 31 December 1930 from Oppenheim to Jacob Gould Schurman, a former President of Cornell and former U.S. Ambassador to Germany (1925–1929), and a few days later, a note to an agent of the German Consulate-General in Chicago, in which Oppenheim imagines a completely new presentation of his finds: “It would be easy to reconstruct the interesting old Temple Palace of Tell Halaf, with its façade statues, as the building in which the treasures would be housed! That would be something fantastic, grandiose, completely original.”

11 Ibid. Also Teichmann, Faszination Orient, pp. 82–83. By vesting order 1330 (27 April 1943), the orthostats came into the hands of the Alien Property Custodian, an agency of the U.S. government, and were put up for sale in October 1943. As the Metropolitan Museum in New York and the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore were the highest bidders, the orthostats went to them. The Metropolitan paid $4,000 for its four orthostats. My thanks to Dr. Yelena Rakic of the Near Eastern Department at the Metropolitan Museum in New York for tracking down the fate of the orthostats left in the Hahn Brothers’ warehouse. See http://www.archives.gov/iwg/declassified-records/rgs-60–131–204-justice/rg-131-case-files.html#335

12 Teichmann, Faszination Orient, p. 84.

13 See Teichmann, Faszination Orient, pp. 85–93.