8. Mongghul Ha Clan Oral History Documentation

DOI: 10.111647/OBP.0032.09.

If you take the wishes of your parents to heart, there won’t be any unfriendly brothers;

If you take the wishes of your ancestors to heart, there won’t be any inharmonious clansmen.2

The Mongghul

The Mongghul (Monguor, Tu) are one of several groups of people who are collectively classified as the Tu nationality in China, where they are one of fifty-six officially recognised ethnic groups. “Mongghul” is a phonetic transcription of the self-appellation of certain groups of Tu living in Huzhu Tu Autonomous County, Ledu County, and Datong Hui and Tu Autonomous County in Qinghai Province; and in Tianzhu Tibetan Autonomous County, Gansu Province. Certain Mongghul elders refer to themselves as Qighaan “White” Mongghul and refer to Mongols as Hara “Black” Mongghul. Some Tibetans refer to them as “Hor”, while Chinese and Hui used “Tu ren” and “Tu min”, both meaning “Tu people” (Chen et al. 2005: 1), before the official designation “Tu” was created after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

In 2011, many classified as Tu born around 1980 or later, refer to themselves as “Tu” as a result of the near universal education system in Chinese, the official designation of Tu, being monolingual in Chinese, the possession of identity cards specifying their ethnicity as Tu, and their ethnicity stated as “Tu” in matters of official administration.

There are a number of early works on the Monguor. These include Mostaert and de Smedt (1929, 1930, 1931), Schröder (1952/1953, 1959, 1964, 1970), and Schram (2006 [1954–1961]). More recently, the diversity of the Tu nationality has been demonstrated by studies and collections related to the Tu living in Tongren County, Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Qinghai Province (Janhunen et al. 2006, Fried 2009, Fried 2010); and Shaowa Tu Autonomous Township, Zhuoni (Janhunen et al. 2007). In addition there have been studies focusing on the Huzhu and Tianzhu Tu (Ha and Stuart 2006, 2008, Ha 2007, Faehndrich 2007); and the Mangghuer of Minhe Hui and Tu Autonomous County, Qinghai Province (Slater 2003).

Authorship in Chinese by PRC writers on the Tu, with the Tu imagined as a single homogeneous ethnicity, has generally focused on history and origins using historical Chinese-language texts, with few in-depth local studies utilising community elders’ knowledge. This tendency to write Tu history using written texts that are often unclear partly explains multiple, competing interpretations. These writings generally make a connection with the Tuyuhun and Xianbei, who are represented as Tu ancestors (Lü 2002, Hu 2010), or arguments are presented that the Tu are descended from Mongol troops who came to the current Qinghai-Gansu area during the time of the Mongol conquests, the Shatuo,3 and Han Chinese (Li 2004, Li and Li 2005). In contrast, the oral history documentation project of the Mongghul Ha Clan4 prioritised the value of local oral history as told by community elders with the goal of making it available worldwide to anyone with an interest, including future generations of Tu people.

It is important to note that migrations, intermingling, and identity transformation of nationalities have been frequent in the Qinghai-Gansu frontier region, making it challenging to claim that the Tu ethnicity is unambiguously derived from a single ancestral group. Disputes and the generation of academic papers regarding Monguor origins are likely to robustly continue. This is due in part to the complicated genesis of the ethnicity of the Tu, and the manner in which the Tu category was created in new China. The dearth of material utilising the knowledge of living illiterate elders and such materials as local clan chronicles emphasises how contemporary Chinese historiography has so often neglected knowledge passed down from generation to generation. Such materials can provide vital information and allow for a more nuanced view of ethnic history.

In terms of Monguor clan histories, Louis Schram’s work on the Liancheng Lu Clan (2006 [1954–1961]),5 and Li and Li’s research (2008) are noteworthy in using clan chronicles to examine the history of the ethnicity. As Nietupski notes, Schram “provides a record of ethnic Monguor clan lineage from its own perspective and gives detail about the tusi6 office and heritage” (2006: 35). Schram’s work suggests that the Lu Clan is of Mongol imperial origin. Li and Li’s book (2008), which makes frequent use of Schram, combines local chronicles with historical Chinese language materials providing further particulars about Mongghul clan origins, especially the two Mongghul Li clans, one of which they claim is of Mongol origin and one of Shatuo origin.

Recording and preserving what living Mongghul elders know of their own history is an urgent task. They are the last group able to repeat generationally transmitted knowledge about clan origins, migration routes, settlement areas, important local figures, and clan genealogy, as well as modes of livelihood, relationships local people had with government, and cultural expression. In addition, they have a rich orally transmitted repertoire of songs, folktales, proverbs, and knowledge of various cultural expressions that are of great importance in illuminating the history of cultural origins, interrelationships, and language studies. The exigency of recording such information is further emphasised by the realisation that very little of this knowledge is being recorded, the heritage-bearers are rapidly passing away, and that the younger generations possess little of this knowledge.

In recognition of these issues and the value placed on living elders’ knowledge, we chose the Ha Clan (two authors’ clan) to study, and make such knowledge publicly available.7

The Mongghul Ha Clan is not mentioned as a Mongghul clan in any written historical sources that we have identified. Is this due to ignorance of such historical sources, or the claim by many contemporary West Ha Clan members that “we were originally not Mongghul” refers to historical fact? To answer these questions and gain further insight into Ha Clan history, the project focused on oral history and family chronicles that survived New China’s chaotic early history.

The Mongghul Ha Clan chronicle

Family chronicles found in China often provide valuable information unrecorded in official history writings. The Hawan Ha Clan chronicle consists of two parts written in Chinese. The first is the Old Chronicle composed in the seventeenth year of the Guangxu Reign (1875–1908) of the late Qing Dynasty.8 The New Chronicle was composed in 1992 and 1993 as a continuation of the Old Chronicle.9 Two sections of the Old Chronicle have survived. The first is a six-page preface and the second is a forty-eight page chronological listing of clan members’ biographies that record birth and death dates, place of interments, and very brief life narratives. This information allows descendants to know where and when visits should be paid to their ancestors’ graveyards.

Originally a genealogical registry of the clan’s ancestors existed called zongnan in the local Chinese dialect, or zong’an in Modern Standard Chinese. It was, according to clan elders, a large piece of cloth that covered nearly one wall of a room. The clan ancestors’ names were written and their portraits sketched on the zongnan, which co-existed with family chronicles. The Ha Clan zongnan, the oldest known record of the clan and the only copy that existed, was destroyed in 1958 during Pochu mixin yundong “Destroy Superstition Movement”.10 The New Chronicle records the following with regard to the zongnan: “We formerly had a roll of white silk cloth that was more than three meters long and 1.6 meters wide called zongnan. It featured our ancestors’ sketches. Among them the most prominent was that of Yinxi Taiye”.11 Another section of the New Chronicle gives generation names that help clan members understand relationships to other clan members. Such relationships are of fundamental significance in Mongghul social structure, where social position in the local community is determined by the generation one belongs to. For example, where one should sit at a wedding ritual where guests are seated according to their generation, the order of the families one visits during the Chinese lunar New Year period, terms of address used for family members in the homes visited, and the order in which liquor is offered, are determined by generation and age. This unified system of generation names differentiates generations by means of a word in every clan member’s name. For example, in the names of two of the chapter’s authors “Ha” is the surname and “Ming” indicates their generation (which is the same). Only the third character in this case is unique, “zong” and “zhu”. This unified system is used both in the West and East Ha Clans (Ha 2007).

Figure 1. Old Chronicle of the Mongghul Ha Clan in Hawan Village. Photograph by Ha Mingzong, 2009.

People with the surname Ha are found among Hui, Mongolian, Tu, and Han ethnicities.12 The Mongghul Ha Clan zongnan’s destruction was a serious blow to the study of its origins; the New Chronicle that was created about thirty-five years later is largely based on elders’ recollections. Regarding clan origins, the New Chronicle preface reads:

In terms of Ha Clan history, the clan originated from Zhuji Street in today’s Nanjing City. In 1376, two brothers moved to Huangzhong and then soon moved to Halazhigou in Huzhu County. The elder brother settled on the west side of the river, and hence the origin of the West Ha Clan. The younger brother settled on the east side, and hence the origin of the East Ha Clan.13

The accounts of Qinghai natives having originated from Nanjing are many among both Mongghul and Han and, perhaps, the account of Mongghul Nanjing origins was created relatively recently (Schram 2006 [1954]: 125, 164). Such an account is absent from the surviving pages of the Old Chronicle. In any case, all the Ha Clan consultants interviewed during this project stated that their ancestors originated in Nanjing.

The Digital Version of Ha Clan History14 suggests that people with the surname Ha in China descended from two brothers—Hala Buding and Hala Buda—who were of Karluk/Geluolu (Halalu) origin and were military commanders of the Oirat Khaan Esen Taiji. Their surname, Ha Baocheng writes, is a phonetic transcription of the first syllable of their own non-Chinese names (personal communication, 2010).

In 1452, the two brothers moved to central China—Zhongyuan—where they became renowned military generals of the Ming (1368–1644) court. The surname Ha became first known in China during this period.

The son of the elder brother, Hala Buding, later moved from Nanjing to Hejian—in today’s Hebei Province—and became the most prominent military general in Hejian following his father’s death. The younger brother, Hala Buda, remained in Nanjing and became a prominent military officer. During this period the Ha Clan divided into two parts: one moved north and lived in Hejian and the other stayed in Nanjing. Ha Baocheng also wrote in personal communication to Ha Mingzong that most of those with the surname Ha in today’s Qinghai and Gansu provinces migrated to these locations from Nanjing during the Ming Dynasty.

It should be noted that the New Chronicle states that Ha Clan ancestors moved from Nanjing to Qinghai in 1376. Ha Baocheng’s research suggests the Hala brothers came first to Nanjing in 1452, which he states is the approximate time of Ha Clan origins in China. There is thus obvious discrepancy in Ha Baocheng’s findings and the New Chronicle. Ha Baocheng also suggests that most Mongghul Ha Clan members in today’s Qinghai and Gansu were originally Han and later were classified as Tu when the Chinese government began establishing minority autonomous regions in the 1950s and the local government in today’s Huzhu needed more people in the Tu ethnic category in order to establish an autonomous county in Huzhu.

The two villages with the most Ha Clan members in Huzhu County are Xihajia Village where, in 2009, there were seventy-eight families (about 380 people) of whom only two families were from another clan. The second village is Donghajia where, in 2009, there were forty families (approximately 220 people) of whom three families were from other clans. Xihajia Village residents with the surname Ha were all classified as Han, while Donghajia Village residents with the surname Ha were all classified as Tu. Ha Clan members in Hawan Village are also registered as Tu.

Migration from Huzhu to Tianzhu

From the late nineteenth century when the Gansu frontier was ruled by Ma Qi (1869–1931) and his son, Ma Bufang (1903–1975), Xihajia was under the jurisdiction of Xining Fu, or “Xining Administration”.

Part of the Xihajia Ha Clan moved to Hawan in three phases from 1918 to 1942. Others moved to Yetu and Dakeshidan villages in Tiantang Town, Xidatan Township; and Anyuan Town in Tianzhu County.15 The digital collection of information related to these migrations, based on interviews with local clan elders, was a major project focus. The initial migration of part of the Xihajia Village Ha Clan occurred in 1918 when Ha Nangsuo moved his family to Hawan as the result of Ma Qi’s efforts to increase the size of his army by forcibly drafting men into his service.16 According to Chen (2009: 13), salaries and supplies for his army were originally provided by the Gansu government, but after Ma Qi became increasingly autonomous, government support ended and he began collecting money and property from the citizenry. Later, when Ma Bufang (known locally as Tu Huangdi “Local King”) came to power, drafting men into the army intensified and taxes increased (Li and Li 2005: 302–304).

According to stories told by elders interviewed, Ma Bufang ordered Mongghul women to stop wearing headdresses and other traditional clothing. Those who refused were vilified and sometimes beaten. Elders said they dared not speak Mongghul within earshot of Ma Bufang soldiers, for fear of punishment. Consultants also said that Ma Bufang conscripted local carpenters, blacksmiths, and masons because of their specialised skills. For example, the interviewee Ha Baode (b. 1939) mentioned that his father, a carpenter fearful of being captured by Ma Bufang’s soldiers, frequently stayed away from home working in such areas as the contemporary Tianzhu County, where Ma Bufang’s influence was less great. When he had accumulated enough money to build a new house in Hawan, he moved his family there. Elders also stated boys and men aged fifteen to fifty were forced into Ma Bufang’s army; such conscriptions were implemented two or three times annually, leaving only old people, women, and children in the village. It was under such circumstances that many Hawan Ha Clan members’ ancestors along with many other people fled to Tianzhu and also why many Tianzhu residents speak the Qinghai Chinese dialect today.

Figure 2. Interview with Gazangshiji (front row, third from left, b. 1932) and Wushisan (second from right, b. 1947) at Gazangshiji’s home in Dakeshidan Village, Tiantang, Tianzhu, Gansu Province, China, in August, 2009. Photograph by Ha Mingzong, 2009.

Figure 3. Interview with Ha Baode (right, b. 1939) and his grandson Ha Mingshan (middle, b. 1997) at their home in Hawan Village in September, 2009. Photograph by Ha Mingzong, 2009.

Figure 4. Interview with Layeshiji (1946–2007) and Lan Jiraqog (b. 1927) at Lan Jiraqog’s home in Hawan Village in February 2005. Photograph by Ha Mingzong, 2005.

Figure 5. Interview with Ha Shenglin (1942–2009) at his home, Hawan Village, in February, 2005. Photograph by Ha Mingzong, 2005.

The current situation of the Mongghul Ha Clan

As discussed earlier, Mongghul Ha Clan members who are originally from Huzhu County live in Xihajia and Donghajia villages in Danma Town, Huzhu County. In Tianzhu Tibetan Autonomous County, Ha Clan members dwell in Yetu, Hawan, and Dakeshidan villages of Tiantang Town, Anyuan Town, Xidatan Township, and Huazangsi Town.

Communication between the modern-day Gansu and Qinghai branches of the Ha Clan has been intermittent over the years. Several Hawan elders have visited their ancestral home in Xihajia and the clan cemetery. Apart from a decreasing number of elders, few Ha Clan members understand that less than a century ago, a clan branch moved to Hawan. When asked to explain this lack of communication, the answer was typically, “We don’t know anybody there”.

Several elders in Xihajia Village speak Mongghul while all others speak only the local Chinese dialect. The linguistic situation is very different in Donghajia Village where nearly everyone speaks Mongghul. Only a fifteen minute walk across a riverbed and a road that leads to Xining separates the two villages, raising the issue of why such a difference in villagers’ knowledge of Mongghul developed. Local accounts suggest that a Xihajia villager known as Hajia Xiansheng “Ha Clan Master” was educated in the Chinese language, thought highly of the importance of Chinese, and encouraged fellow villagers to speak and learn this language. Other reasons remain unclear for this startling difference in language abilities between the two nearby villages of the same clan.

Historically, the inconvenience of travel made the distances separating various Ha Clan settlements difficult and thus cross-community visits were impractical and communication sporadic. Over the years, differences between these settlements have developed. For example, all Xihajia residents are registered as Han, speak the local Chinese dialect, and follow local Chinese marriage and burial ceremonies, whereas people in Donghajia are registered as Tu, speak Mongghul, cremate their dead, and sing Mongghul songs at weddings. Ha Clan people in Hawan, though of Xihajia descent, speak Mongghul, while the generation born around 1990 have varying ability in understanding and speaking Mongghul. Most Hawan Mongghul, in 2011, spoke Chinese more often than Mongghul, no longer wore Mongghul clothing, nor sang in Mongghul, and generally felt there was little difference between Tu and local Han.

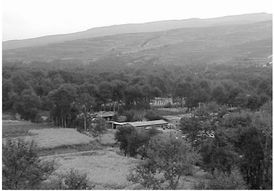

Figure 6. Xihajia Village: Home-village of the Mongghul Ha Clan in Hawan Village. Photograph by Ha Mingzong, 2009.

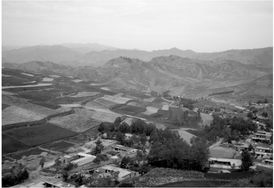

Figure 7. Hawan Village. Ha Mingzong and Ha Mingzhu’s home village. Photograph by Ha Mingzong, 2008.

For the entire West Ha Clan, the Mongghul language is maintained only in Hawan Village. The number of Mongghul speakers is decreasing rapidly in Hawan because more children go to schools where the only language used is Chinese, villagers go to other areas for long periods of the year to work where Chinese is the lingua franca, and on account of an increasing number of marriages with Chinese and Tibetan women who do not speak Mongghul.

Project approaches

An inspiration for undertaking this project was the debate over the issue of Tu history. We felt that Mongghul elders had important information and we were determined to bring to life and permanently record their stories and thoughts as it often differs from texts focusing exclusively on written sources. We also felt a responsibility to future generations of Mongghul youth to provide a record of their ancestors’ memories. Consequently, Ha Mingzong and Ha Mingzhu visited Mongghul Ha Clan members in Xihajia and Donghajia villages in Huzhu; Hawan, Yetu, and Dakeshidan villages and Huazangsi Town in Tianzhu; and Akesu in Xinjiang and made audio and video recordings of interviews. This information was easily copied onto DVDs and VCDs which, as Gerald Roche et al. comment, fit into “the video-disc (VCD) era of today” because almost every village family has a VCD or DVD player (2010: 154). Community elders were enthusiastic about the audio-video documentation of their family stories for posterity.

Local reactions

The project elicited different points of view among locals. Villagers from all the Ha Clan communities that we visited welcomed us: an expression of their code of hospitality. After explaining the purpose of our visit, elders encouraged us with comments on the importance of the preservation of family oral history. Elders understand that after they pass away, most of their cultural knowledge and memories will also vanish. Clan elders also thought highly of the idea of producing DVDs and VCDs from the interviews to supplement information in the clan chronicles.

In contrast, the younger generation was largely indifferent, though they were keenly interested in the recording equipment and the idea of “being on TV”. We sensed considerable scepticism of the project’s importance and practicality. For example, on one occasion as Ha Mingzong was interviewing an elder about family history, a man in his twenties joined us, took Ha Mingzong’s notebook, looked at his notes, put the notebook down with a bored expression, and asked late in the interview what Ha Mingzong’s purpose was in collecting such information. He added that such information did not enhance skills learnt at school and was not helpful in finding employment. When Ha Mingzong replied that he thought that cultural preservation was important, this man asked why Ha Mingzong, who was studying abroad, would choose to study his own people when he had the chance to learn things that could not be acquired at home and besides, he added, many local Mongghul would probably always know more about themselves than he would.

Ha Mingzong and Ha Mingzhu’s family and relatives generally did not understand why they were involved in such projects that focused on an intensely impoverished past and present reality that many people spend a lifetime trying to escape. Such reactions and attitudes reflect a concern that activity should deliver a monetary reward quickly: cultural documentation is not seen as providing financial benefit.

Project outcome

Ha’s Mongghul Ha Clan Oral History (2010) was based on oral interviews and contributes to the study of Mongghul history by presenting a digital, oral history of the Mongghul Ha Clan. Ha Clan elders surprised us by suggesting a possible origin of the Mongghul Ha Clan from Nanjing in south China. The project also resulted in a transcribed, translated, and glossed interview conducted with Ha Shenglin (Appendix 1) that gives information on family history, childhood, clan migration, and religious beliefs and thus has historical, ethnographic, and ethnolinguistic value, given the dearth of such content in both written and oral texts.

Selected interviews were transcribed using the Transcriber program that allows preservation and presentation of both the audio file and the transcription, allowing for the oral text to be presented simultaneously with the corresponding transcription. This permits readers to follow the exact transcription while listening to the recording. A screenshot of such transcriptions may be seen in Appendix 2.

DVDs and VCDs were produced from interviews and activities filmed, and given to community members, including the interviewees, who received not only their own interviews, but also interviews from other Ha Clan villages. These compact discs hold both images and voices, preserving memories of people, places, and a certain time in history, providing clan members with heretofore unknown information, strengthening a sense of clan unity, and providing locally a unique record of Ha Clan members across Ha Clan communities. These were all major project goals.17

A participatory approach to cultural documentation was used, prioritising the value of local oral history as related by community elders, making it available worldwide to anyone interested and with an Internet connection. By digitally documenting and presenting the oral history of a relatively large Mongghul clan living across an extended area, new historical insights into Tu history became available. This is obvious in the death of Ha Shenglin. At present, no one in his immediate family knows the details of his father’s and grandfathers’ lives; information that was recorded by Ha Mingzong is now available.

The lives of contemporary Tu youth are increasingly influenced by images of a privileged life lived by China’s elite and in the West, and modern global pop culture such as Korean soap operas that have been popularised through the ubiquity of television, compact video discs, and the Internet. There is extreme poverty in some of the most traditional Mongghul communities, evident through lack of access to basic health care and resources that would pay for such care, clothing that is plain and simple, and an education system that is dramatically inferior to that available in such urban centres as Xining and Lanzhou. Knowledge of oral history and Mongghul songs, wearing Mongghul clothing, and a profound knowledge of local Mongghul history do not give most Mongghul youth a sense of belonging to a glittery attractive global pop culture. It is the latter to which they aspire: to be able to dance, sing, and dress like pop icons, and enjoy an affluent life.

However, as the decades pass and people’s lives continue to improve economically and become increasingly synonymous with global urban culture, future Mongghul generations may search for their roots in an effort to distinguish themselves from much of the rest of humanity. To conclude, we offer this account by Ha Mingzong:

I was born and raised in Hawan Village, a Mongghul village, which was surrounded by Chinese speaking Han, Hui, and Tibetans. All villagers in Hawan speak Chinese and, in the late 1990s, all could also speak Mongghul.

Villagers switched between languages when they talked to each other. I lived in the village during the first fifteen years of my life and never heard a fellow villager sing in Mongghul.

I attended schools where classes were taught in Chinese, and where Han, Hui, Tibetan, and Mongghul students and teachers all spoke Chinese. Raised in such an environment led me to believe there were no appreciable differences between local Chinese, Tibetans, and my Mongghul community, other than I spoke an additional language, since most local Tibetans in Tianzhu only spoke Chinese. It never occurred to me that there was a gap in our thinking and behaviour.

This attitude changed in 2002 when, at the age of sixteen, I enrolled in the ETP (English Training Program) at Qinghai Normal University, a programme initiated in 1997. I was the lone non-Tibetan in a class of students from Qinghai, Sichuan, Yunnan, Gansu, and the Tibet Autonomous Region. I quickly realised that I was different from my Tibetan classmates for they all spoke languages I did not understand. Some classmates thought I was a Han Chinese teenager who happened to speak Mongghul. I was singled out for a long time. A part of me felt proud that I was different, but I was not proud of knowing little about Mongghul culture. There were occasions when we were asked to sing traditional songs and I was put in an awkward situation because I could not sing any Mongghul songs, unlike my Tibetan friends, many of whom knew many traditional songs.

I then wished to know more about Mongghul culture. That was why I was very pleased when I was introduced to an older Mongghul folk researcher and started doing cultural preservation projects. I wanted to learn more about my culture in the process. And I did. I borrowed CDs and VCDs of recorded Mongghul folk songs and learned them. I also began digitally documenting Mongghul folklore from many Mongghul villages and distributing the materials back to the local communities, including my own, where such recordings sometimes brought tears to the eyes of old people who dearly appreciated them and the memories they resurrected after having been surrounded by pop music for years.

Based on my experience, it is important to know a great deal about Mongghul culture in order to be proud of being Mongghul, because this brings knowledge about what there is to be proud of, which leads to confidence in being Mongghul. Time spent studying Mongghul culture and history is solely up to the individual; it is not taught in any schools.

My experience in cultural preservation has allowed me to discover my people and, in so doing, I have more fully discovered myself: a road less travelled that has already taken me much farther than I ever expected.

Appendix 1: Transcription, Translation and Glossing

Location: |

Ha Shenglin’s home, Hawan Village, Tiantang Township, Tianzhu Tibetan Autonomous County, Wuwei Region, Gansu Province, China |

Date:18 February 2005

Interviewer:Ha Mingzong (A)

Interviewee:Ha Shenglin (B)

1. Family Members

(1)A: |

Uh, |

aadee18 |

niudur |

saa, |

|

HES |

granduncle |

today |

PRT |

Bu |

qi-mu-la |

nige |

tangxaa-le-la |

ire-wa. |

1s |

2s-ACC-COM |

one |

chat-VBLZR-PURP |

come-PERF |

Uh, Granduncle, today I have come to have a chat with you.

(2)B: |

Sain-na. |

|

Good-OBJ.NARR |

Good.

Yaan |

tangxaa-le-genii |

ge-sa, |

|

|

what |

chat-VBLZR-SUBJ.FUT |

QUOTE-COND |

diijuu |

Haja |

kun-ni |

Lishi19-ni |

actually |

Ha.Clan |

people-GEN |

history-ACC |

nige |

tangxaa-le-la |

ire-wa |

bai. |

one |

chat-VBLZR-PURP |

come-PERF |

PRT |

What I am here to talk about is actually the history of Ha Clan people

(4)B: |

Au…au, |

dui |

dui |

dui…. |

|

AGREE |

right |

right |

right |

Oh, right, right, right…

(5)A: |

qi-mu, |

qi |

qi-ni |

nara-ni, |

qi |

nige |

kile |

bai. |

|

2s-ACC |

2s |

2s-GEN |

name-ACC |

2s |

one |

say |

PRT |

Please, you, tell (me) your name.

(6)B: |

Mu-ni |

nara |

maa? |

|

1s-GEN |

name |

QUEST |

My name?

(7)A: |

Uh. |

|

AGREE |

Yes.

Nara |

si |

diijuu, |

uh… |

qidar-la |

hao,20 |

|

|

Name |

COP |

actually |

HES |

Chinese-INSTR |

PRT |

uh… |

yaan-na |

bai, |

Ha |

Shenglin-na |

bai. |

HES |

what-OBJ.NARR |

PRT |

Ha |

Shenglin-OBJ.NARR |

PRT |

Mongghul-la |

hao |

dii |

mu-ni |

nara |

si |

Mongghul-INSTR |

PRT |

then |

1s-GEN |

name |

COP |

Bu |

Uje-ya |

yaan-na |

saa? |

1s |

See-VOL |

what-OBJ.NARR |

PRT.quest |

Uh, |

ndaa |

si, |

(interference…) |

HES |

me |

COP |

|

Niangniang |

ndaa |

bao-ki-ja |

bai, |

Niangniang |

me(ACC) |

protect-VBLZR-OBJ.PERF |

PRT |

Bao’ai |

Wa |

bai. |

Bao’ai |

OBJ.COP |

PRT |

My name, actually in Chinese is Ha Shenglin and in Mongghul, it is, let me see, uh, what is it? Bao’ai, since Niangniang protected me.

Appendix 2: Transcription and Translation

Synced transcription and translation of an interview (audio file) using Transcriber.

Appendix 3: Selected Transcriptions of People and Places

A

Akesu

Anyuan Town

B

Beijing

D

Dakeshidan

Danma Town

Datong Hui and Tu Autonomous County

Donghajia Village

E

Emperor Qianlong

G

Gansu Province

Guangxu

H

Ha Baocheng

Ha Baode

Ha Mingshan

Ha Nangsuo

Ha Shenglin

Hajia Xiansheng (Ha Clan Master)

Hala Buda

Hala Buding

Halalu

Halazhigou

Han Chinese

Hawan Mongghul Ha Clan

Hejian

Huangnan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture

Huangzhong

Huazangsi Town

Hui

Huzhu Tu Autonomous County

K

Karluk/Geluolu

L

Ledu County

Liancheng Lu Clan

M

Ma Bufang

Ma Qi

Ming court

Minhe Hui and Tu Autonomous County

Mongghul Li clan

N

Nanjing City

P

Pochu mixin yundong (Destroy Superstition Movement)

Posijiu (Smash the Four Olds)

Q

Qing

Qinghai Province

S

Shaowa Tu Autonomous Township

Sichuan

Smash the Four Olds

Tiantang Town

Tianzhu Tibetan Autonomous County

Tibet Autonomous Region

Tongren County

Tu Huangdi  (local name for Ma Bufang “Local King”)

(local name for Ma Bufang “Local King”)

Tu min (Tu people)

Tu ren (Tu people)

Tu

Tuyuhun

W

Wushisan

X

Xianbei

Xidatan Township

Xihajia Village

Xihajia

Xining Fu (Xining Administration )

Xinjiang

Y

Yetu

Yinxi Taiye

Yinxi

Yongdeng County

Yunnan

Z

Zhongyuan

Zhuji Street

Zhuoni

zongnan/ zong’an (genealogical registry)

Chen, Zhaojun and Xinghong Li et al., Folktales of China’s Minhe Mangghuer (Muenchen: Lincom Europa, 2005).

Chen, Bingyuan  , Ma Bufang jiazu tongzhi qinghai sishi nian

, Ma Bufang jiazu tongzhi qinghai sishi nian  , (Xining

, (Xining  : Qinghai renmin chubanshe

: Qinghai renmin chubanshe  ) [Ma Bufang Family’s Forty Year Reign in Qinghai (Xining: Qinghai People’s Press, 2007)]

) [Ma Bufang Family’s Forty Year Reign in Qinghai (Xining: Qinghai People’s Press, 2007)]

Faehndrich, Burgel R. M., Sketch Grammar of the Karlong Variety of Mongghul, and dialectal Survey of Mongghul (unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Hawaii, 2007).

Fried, Mary Heather Yazak, Dressing Up, Dressing Down: Ethnic Identity Among the Tongren Tu of Northwest China (unpublished doctoral dissertation, State University of New York, 2009).

Fried, Robert Wayne, A Grammar of Bao’an Tu, A Mongolic Language or Northwest China (unpublished doctoral dissertation, State University of New York, 2010).

Ha, Baocheng  , Hashi zuqun de lishi dianziban

, Hashi zuqun de lishi dianziban  [Digital Version of the Ha Clan History] (unpublished recording, 2010).

[Digital Version of the Ha Clan History] (unpublished recording, 2010).

Ha, Mingzong, and C. K. Stuart, ‘Everyday Hawan Mongghul’, Mongolica Pragensia, 06 (2006), 45–70.

—, and C. K. Stuart, ‘The return of the Goddess: Religious Revival among Hawan Village Mongghuls’, Mongolo-Tibetica Pragensia, 1 (2) (2008), 117–148.

—, ‘Politeness in Hawan Mongghul’, Mongolica Pragensia, 07 (2007), 29–54.

—, Interview with Ha Shenglin, Hawan (Gansu, China, February 2005).

—, Interview with Ha Baode, Hawan (Gansu, China, September 2009).

—, Interview with Ha Zhanyuan, Xihajia (Qinghai, China, September 2009a).

—, Interview with Ha Shengcheng, Huazangsi (Gansu, China, September 2009b).

—, Interview with Gazangshiji and Wushisan, Dakeshidan (Gansu, China, September 2009c).

—, Interview with Ha Shenghui, Ha Shengcheng and Lan Deke, Hawan (Gansu, China, September 2009d).

—, ‘Orální historie mongghulského rodu Ha’ [Mongghul Ha Clan Oral History] (unpublished bachelor’s thesis, Charles University Prague, 2010).

—, Interview with Ha Lianying, Akesu (Xinjiang, China, July 2010).

—, Interview with Ha Shengcai, Ha Shengzhang, and Ha Baoshan, Hawan (Gansu, China, August, 2011).

Ha, Shoude  and Li Zhanzhong

and Li Zhanzhong  , Tianzhu tuzu

, Tianzhu tuzu  , (Tianzhu

, (Tianzhu  : Tianzhu zangzu zizhixian minzu chubanshe

: Tianzhu zangzu zizhixian minzu chubanshe  ) [Tianzhu Mongghul, (Tianzhu: People’s Press of Tianzhu Tibetan Autonomous County, 1999)].

) [Tianzhu Mongghul, (Tianzhu: People’s Press of Tianzhu Tibetan Autonomous County, 1999)].

Hu, Alex, ‘An Overview of the History and Culture of the Xianbei (‘Monguor’/’Tu’)’, Asian Ethnicity, 11 (1) (2010), 95–146.

Janhunen, Juha and Ha Mingzong et al., ‘On the Language of the Shaowa Tuzu in the Context of the Ethnic Taxonomy of Amdo Qinghai’, Central Asiatic Journal, 51 (2) (2007), 177–195.

Janhunen, Juha, ed., The Mongolic Languages (London and New York: Routledge, 2003).

—, ‘The Monguor: The Emerging Diversity of a Vanishing People’, in The Monguors of the Kansu-Tibetan Frontier, by Louis M. J. Schram, ed. by Charles Kevin Stuart (Xining City: Plateau Publications, 2006), pp. 26–29.

—, and M. Peltomaa et al., Wutun (München: Lincom Europa, 2008).

Li, Shenghua  , ‘Tuzu juefei tuyuhun houyi

, ‘Tuzu juefei tuyuhun houyi  ’ [‘The Tu people are not Tuyuhun descendants’], Qinghai Social Sciences

’ [‘The Tu people are not Tuyuhun descendants’], Qinghai Social Sciences  , 4 (2004), 149–160.

, 4 (2004), 149–160.

Li, Keyu , and Li, Meiling

, and Li, Meiling , Hehuang menggu’er ren

, Hehuang menggu’er ren  (Xining

(Xining  : Qinghai renmin chubanshe

: Qinghai renmin chubanshe  ) [Hehuang Mongols (Xining: Qinghai People’s Press, 2005)].

) [Hehuang Mongols (Xining: Qinghai People’s Press, 2005)].

Li, Zhanzhong  and Wangxiang Yan

and Wangxiang Yan  et al., Gansu tuzu wenhua xingtai yu guji wencun

et al., Gansu tuzu wenhua xingtai yu guji wencun  . Gansu shaoshu minzu guji congshu

. Gansu shaoshu minzu guji congshu  (Lanzhou

(Lanzhou : Gansu minzu chubanshe

: Gansu minzu chubanshe  ) [Culture Configuration and Historical Records of Gansu Tu Nationality. Historical Records of Nationalities in Gansu (Lanzhou: Gansu Nationalities Press, 2004)].

) [Culture Configuration and Historical Records of Gansu Tu Nationality. Historical Records of Nationalities in Gansu (Lanzhou: Gansu Nationalities Press, 2004)].

Limusishiden, (Li Dechun) and C K Stuart, ‘Relevance to Current Monguor Ethnographic Research’, in The Monguors of the Kansu-Tibetan Frontier, by Louis M. J. Schram, ed. by Charles Kevin Stuart (Xining City: Plateau Publications, 2006), pp. 60–79.

Lü, Jianfu  , Tuzu shi

, Tuzu shi  , (Beijing

, (Beijing  : Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe

: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe  ) [Tu History (Beijing: Chinese Social Sciences Press, 2002)].

) [Tu History (Beijing: Chinese Social Sciences Press, 2002)].

Mostaert, Antoine and A. de Smedt, ‘Le dialecte Monguor parlé par les Mongols du Kansu Occidental (I+II)’, Anthropos, 24 (1929), 145–65, 801–815.

—, ‘Le dialecte Monguor parlé par les Mongols du Kansu Occidental (III+IV)’, Anthropos, 25 (1930), 657–69, 961–973.

—, ‘Le dialecte Monguor parlé par les Mongols du Kansu Occidental (V)’, Anthropos, 26 (1931), 253–254.

Nietupski, Paul, ‘Louis Schram and the Study of Social and Political History’, in The Monguors of the Kansu-Tibetan Frontier, by Louis M. J. Schram, ed. by Charles Kevin Stuart (Xining City: Plateau Publications, 2006), pp. 30–36.

Roche, Gerald and Ban+de mkhar et al., ‘Participatory Culture Documentation on the Tibetan Plateau’, in Language Documentation and Description, Vol 8, ed. by Imogen Gunn and Mark Turin (London: SOAS, 2010), pp. 147–165.

Sagaster, Klaus, ‘The Mongols of Kansu and their Language’, in Antoine Mostaert, Vol. 2, ed. by Klaus Sagaster (Ferdinant Verbiest Foundation: Leuven, 1999) pp. 175-190.

Schram, Louis M. J., The Monguors of the Kansu-Tibetan Frontier, Part I: Their Origin, History, and Social Organization; Part II: Their Religious Life; Part III: Records of the Monguor Clans: History of the Monguors in Huangchung and the Chronicles of the Lu Family, ed. by Charles Kevin Stuart (Xining: Plateau Publications 2006 [1954, 1957, 1961]).

Schröder, Dominik, ‘Zur Religion der Tujen des Sininggebietes (Kukunor)’, Anthropos, 47 (1952), 1–79, 620–658, 822–870.

—, ‘Zur Religion der Tujen des Sininggebietes (Kukunor)’, Anthropos, 48 (1953), 202–259.

—, Aus der Volksdichtung der Monguor [From the Popular Poetry of the Monguor]; 1. Teil: Das weibe Glücksschaf (Mythen, Märchen, Lieder) [Part 1. The White Lucky-Sheep (Myths, Fairytales, Songs)]. Asiatische Forschungen 6 (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1959).

—, ‘Der dialekt der Monguor’, in Mongolistik (Handbuch der Orientalistik, 1. Abteilung, 5. Band, 2. Abschnit), ed. by B. Spuler (Leiden: EJ Brill, 1964), pp. 143-158.

—, Aus der Volksdichtung der Monguor [From the Popular Poetry of the Monguor]; 2. Teil: In den Tagen der Urzeit (Ein Mythus vom Licht und vom Leben) [Part 2. In the Days of Primeval Times (A Myth of Light and Life)] (Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz, 1970).

Slater, Keith W., A Grammar of Mangghuer: A Mongolic Language of China’s Qinghai-Gansu Sprachbund (New York: Routledge Curzon, 2003).

—, ‘Mangghuer’, in The Mongolic Languages, ed. by Juha Janhunen (London and New York: Routledge, 2003a), pp. 307–324.

Stuart, Charles Kevin, and Limusishiden (Li Dechun), ‘China’s Monguor Minority: Ethnography and Folktales’, Sino-Platonic Papers, 59 (1994).

Online Sources

Ha Baocheng, A Digital Version of Ha Clan History

<http://hbcdata.home.news.cn/blog/>

Website about Tu people

<http://www.e56.com.cn/system_file/minority/tuzu/lishi.htm>

World Oral Literature Project, Ha Mingzong: Mongghul Ha Clan Oral History

<http://www.oralliterature.org/collections/hmingzong001.html>

Footnotes

1We thank Veronikia Zikmundová, Gerald Roche, and Limusishiden for helpful comments on this chapter.

2Excerpt from the Old Chronicle of the Hawan Mongghul Ha Clan. The verse was originally written by Emperor Qianlong (1711–1799) in the literary work ‘Shengjinfu  ’.

’.

3The Shatuo were a local section of the Ancient Turks (Janhunen, 2006).

4Clan refers here to a group sharing a common surname and a common genealogy or chronicle.

5Liancheng Town is located in contemporary Yongdeng County, Gansu Province.

6Tusi = Chinese-appointed or inherited-post local officials; “hereditary local chief” (Nietupski 2006: 30, 33).

7The Mongghul Ha Clan consists of the West Ha Clan (Mongghul Ha Clan members from or who moved away from Xihajia (West Ha Clan) Village), and East Ha Clan members, who are from or previously were from Donghajia (East Ha Clan) Village, Huzhu County, Qinghai.

8Preface of the Ha Clan’s unpublished Old Chronicle (1892).

9Preface of the Ha Clan’s unpublished New Chronicle (1993).

10Campaigns engendered by Posijiu “Smash the Four Olds” (old customs, culture, habits, and ideas) began in 1966 and resulted in widespread destruction of family chronicles in China.

11Yinxi refers to the tradition of the emperor bestowing titles and ranks to his subjects on the basis of their immediate ancestors having been high-ranking officials and having honorably served the court. “Taiye” literally refers to one’s great-grandfather; it is also an honorific title for an ancestor.

12Ha Baocheng, an independent Hui scholar living in Beijing, has compiled A Digital Version of Ha Clan History, which he shared with Ha Mingzong. Most of the material from this collection is available from his website in Online Sources. Ha Baocheng contends that Hui with the surname Ha originated from the Muslim Khanate of Bukhara.

13Preface of the Ha Clan’s unpublished New Chronicle (1993). Original text:

14See Online Sources

15Data collected by Ha Mingzong during his fieldtrips.

16Schram (2006 [1954–1961]: 306–07) describes nangsuo as an institution originally created by the Ming court in Huangzhong for local lama chiefs to carry out tasks such as “the granting of a territory, the fixing of a yearly tribute, the recognition of the chieftainship of the lama who had brought in the tribe, and of the heritability of that chieftainship”.

17Relevant recordings of Ha Clan oral history are available on the World Oral Literature Project website, Ha Mingzong: Mongghul Ha Clan Oral History (see Online Sources).

18Aadee may refer to a person’s grandfather or any male from the grandfather’s generation.

19Chinese lishi  = Mongghul lorji = Tibetan lo rgyus.

= Mongghul lorji = Tibetan lo rgyus.

20From the local Qinghai Chinese dialect.

, Ha Mingzhu

, Ha Mingzhu  and C. K. Stuart

and C. K. Stuart