IV. Bisa Storytelling: The Politics of Hunting, Beer-Drinks, and Elvis

Then three, a constant visitor is very often the one who turns against you, your friend…

…the one you like is the one who arrests you. Then four, a woman does not keep any secrets. You may have killed an animal in the bush, if a woman had seen it then she will reveal that secret. She will say, “He killed an animal.” (Kabuswe C. Nabwalya, explaining a brief mulumbe, at Nabwalya)

In the 1988–89 academic year at the University of Zambia, I made two trips to Nabwalya in the Luangwa Valley. This region remains one of the largest wildlife preserves in Africa. The people who inhabit the center of the area, between the two parks, are Bisa, and they speak a language that is related to Bemba, though there are some fairly consistent sound shifts and many differences in usage. To accurately describe the conditions surrounding the recording of stories and my reception by the local residents, I need to very briefly explain the position of the Bisa in relation to Zambia’s policies on game management and tourism.

The Bisa120 have lived in this area, referred to as the Munyamadzi Corridor and situated basically between what are today the Luangwa North and Luangwa South game parks, for nearly two centuries. They have always hunted game for food and profit, and they also cultivate some subsistence crops, in particular sorghum. From the time of colonial rule throughout the independence era, officials have tried to preserve wildlife and manage the lands people shared with animals by employing varying policies. In the period immediately following Zambian independence, one commission recommended “relocating” the Bisa in order to insure the preservation of animals that had great economic potential for tourism and safari hunting.121 This relocation was never carried out but it suggests the colonial government’s prioritizing of animals over people at that time. The Bisa live in an area that is very difficult to reach by road, especially during the rainy season, and this isolation has in great part restricted the growth of their communication and transportation infrastructure. This has led to problems in the adequate development of local schools, clinics, retail shops, and postal services. In fact, this relative isolation has kept the Bisa somewhat out of the loop in terms of general socio-economic participation in Zambia’s development.

While the problems of animals living near human habitats are not unique to the Bisa, they are perhaps one of the most obvious targets of government management and conservation programs. To simplify what are a number of competing policy visions, there are two basic schools of thought regarding the regulation of people and animals in such areas. The first harks back to colonial policies, which set out to preserve game and habitats under the structure of “indirect rule,” requiring local chiefs to enforce anti-hunting laws and manage game areas, essentially criminalizing the taking of game that had been a practice long before the arrival of European rule. The other more recent, not entirely dissimilar, school of thought is the empowering of local people to preserve the flora and fauna in their areas by sharing in the profits to be had in the tourist and safari hunting industries. The reasoning behind this approach is that once they are made aware of the potential profits and gains in personal and communal spheres, local people would see the logic in giving up illegal hunting, cooperating with enforcement personnel, and turning to less destructive economic pursuits, such as farming and, perhaps, crafts manufacturing.

The problem of preserving animal populations is widespread in large game parks and preserves in east and southern Africa. There is a great deal of money to be made in tourism and licensed hunting, and the questions about what to do when people and animals compete for the same land are long-standing ones. Due to several international economic developments, particularly the oil boom of the 1970s and 80s, the demand for elephant tusks and rhinoceros horns was fueled by the ability of potential buyers to pay lucrative prices, especially in parts of Asia. The dramatic drop in the numbers of these large mammals in east and central Africa was a major cause of concern for local governments and international conservationists. In the case of the Bisa, just before and after 1988–89, several initiatives were employed to try to control what the government defined as rampant illegal poaching. There ensued a complex set of political struggles at local, national and international levels. Two separately empowered groups were trying to install their own policies and procedures in the situation in the Munyamadzi Corridor. Each was backed by different agencies or entities, with funding for both initiatives coming from a combination of local and international sources.122 While this is not the place to detail the complex of actors and issues pertaining to these conservation efforts, it is relevant to observe that the Bisa were directly in the middle of these initiatives and would find themselves having to mediate, fend off, or cooperate with official representatives and their policies in order to go about their daily lives.

For a long time before this period of dueling programs, government had established and maintained a steady presence in the Bisa area for the purpose of managing wildlife. Game scouts and guards circa 1988–89, more than earlier, kept up a high profile in order to curtail poaching. Less than several hours drive from Nabwalya, across the Luangwa River, are numerous game lodges that cater to a mainly foreign clientele. The revenue generated by tourism in the South Luangwa Park is substantial and the government sees the protection of wildlife, especially the endangered elephant and rhinoceros populations, as vital in the drive to increase this income. Safari hunters pay substantial license fees to be able to come to the area and shoot various types of big and smaller game. The situation is complicated not only by the historical hunting practices of the Bisa, but also by inconsistencies of enforcement policies, the shifts in approaches by the government, the fact that high-priced animals are often poached by well-equipped outsiders—in some cases, rumors and some actual instances suggest, by government officials—and the overall emotional responses to notions of game preservation and the needs of human beings.

Over time, there have simply not been enough sensible and logical incentives and rewards to keep Bisa hunters from plying their trade around Nabwalya. The reasons for this reside in great part in Bisa culture and traditions themselves. Hunting is more than an economic activity that provides meat and/or profit to individuals. It is a practice that is inextricably woven into the way Bisa society defines itself. Again simplifying a more complex set of relationships and dynamics, young Bisa men are linked matrilineally to older men, often uncles or “fathers”, who help them to gain social status and even to carry out courtship and marital activities. These older men often teach others to hunt, supply them with hard to find guns—up until recently, of the muzzle-loading variety—and identify or set up the networks through which game meat is distributed within the lineage. As young hunters become successful and gain prestige and wealth, in the form of wives, land and admiration for their hunting prowess, they eventually become men of status and might even come to head up a section of a village or move out to establish their own small villages. These relationships are complicated by the role and status of the chief, in this case Chief Nabwalya, who on a larger scale warrants gifts of tribute and allegiance, which he then parcels out to others to enforce or initiate relationships of patronage and loyalty.123 Moreover, for some decades in the 1960s to early 1980s, a good number of Bisa men established themselves in the society by migrating to other areas, often the copper mines, for wage labor and returning with financial resources to build a home and support themselves and their families. The declining economy of the 1970s, due in most part to the dramatic fall in international copper prices, meant that this avenue to success was less traveled, spurring recourse to local practices of hunting and strengthening lineage relationships.

When game management policies encountered Bisa life, even more complicated relationships ensued. During the days of colonial rule and the early independence period, when strict enforcement of game laws were in effect, Nabwalya remained so far off the beaten path that the occasional arrest and fining or imprisonment of local hunters had a minimal effect on what most people were doing. When, in the early 1980s, funding was increased for the two competing management schemes, with a concomitant infusion of larger numbers of game guards and scouts, the stakes were dramatically raised for Bisa hunters to pursue their activities. Where in the past, local game enforcement personnel had found paths of coexistence with villagers by only occasionally arresting offenders, sharing meat they legally cropped, and getting to know the locals, the new policies were more aggressive and provided clearer rewards for strict enforcement. In a culture where, from the colonial days on, a rather low key humanistic understanding of looking the other way and mediating things with a view towards peaceful coexistence was common, the harsher methods of enforcement would bring greater uncertainty to the lives of local people. One specific development around 1988 was the new policy of hiring local young men as wildlife scouts. These scouts, who knew and were known by resident Bisa, entailed a new kind of class who were empowered and emboldened to assert their influence in local affairs and at times challenge or subvert traditional sources of social order, such as elder men.

Needless to say, many Bisa are rather suspicious of strangers and tend to keep their distance even from the government officials they do know. Nabwalya is the largest of the Bisa villages in the area, and it is composed of small houses clustered in groups of four to ten and separated from neighboring compounds by at least two to three hundred feet. I first visited Nabwalya in October 1988, at the end of the dry season. At that time people were cutting tall grass and dried sorghum stalks before burning them in preparation for the coming rains. We arrived at the village, after a rather long, somewhat muddy (the first rain of the season had fallen the night before we came), drive over barren and difficult terrain. I was traveling with Stuart Marks, who had just returned to Zambia on a Fulbright award and who at that time had been conducting research in Nabwalya off and on for over twenty years. In our vehicle were two residents of Nabwalya, one a Rural Council postman and the other a judge at the local government court—whom we’d encountered at the game control barrier before descending the escarpment into the Luangwa Valley—and a young anthropologist on her first trip to Zambia. Our group was welcomed on the basis of our Bisa co-travelers and Stuart Marks, who was a well-known and clearly respected presence among the village leaders.

We spent the afternoon moving Stuart’s gear into a newly finished government house, meant for an agricultural officer who had not yet appeared.124 We set screens into the glass-less metal windowpanes, set up a mosquito net in a bedroom, and basically organized the four rooms into a household/office. While this was going on, a young boy came to summon us to a meeting Chief Nabwalya and a village development committee were having with representatives of the provincial government. It is important to note that the government of President Kenneth David Kaunda was about to hold elections. At that time, Zambia was a one-party state (the United National Independence Party, or UNIP) with serious economic and political problems. Part of the reason for this visit was to remind people of the elections and their importance, especially the importance of voting for the president, who was running unopposed. Nabwalya had a year earlier made the international news for requiring emergency aid to stave off famine after overly heavy rains following a drought had combined to wipe out much of their staple sorghum crop. Government officials were sensitive to the negative national and international image perpetuated by such situations and were trying to work with local people to ensure a better harvest and more stable economic conditions. In fact, since the people of Nabwalya had not seen much progress and development under the current government, they certainly were ripe for feelings of disaffection and alienation. The person leading the government group was the Province’s Member of the Central Committee, Mr. L.M. Ng’andu, who was also the Paramount Chief Chitimukulu of the Bemba people. After our presence was explained and we showed our identification, we were allowed to sit through the meeting. One issue that immediately came up was the language in which the talks were to be carried out. Though the Bisa constituents asked that Bemba be spoken, the government representatives insisted that the official language of the country, English, be the medium of discussion. This had the immediate effect of excluding some members of the committee from the conversation.

The village committee had many issues to raise with the provincial representatives. These included the problem that a new school building, to be constructed by local self-help labor, had received glass for its windows that was the wrong size, no recent graduates of the school had been accepted into secondary school, and there was concern over the quality of skills of local teachers. Further, the village had been granted a new vehicle by the World Wildlife Fund to assist with development projects, but this had basically been commandeered by the local game warden. A grinding mill, meant, again, for local self-help in pounding grains such as sorghum into flour, had been promised but never delivered. The list of issues presented by the Ward Chairman was mostly dismissed as district rather than provincial or national concerns. Very little attention was, therefore, given to these matters at the brief gathering.

After the meeting, one which left the Nabwalya committee frustrated and dispirited, feeling that they were having little input into the policies and decisions that affected their lives, we returned to Stuart’s house to finish the move. Refusing the offer of hospitality of the local committee, the government group left before sunset to spend the night in the relative comfort of the quasi-legal game camp of a European working for a government development agency. The group had licenses to kill numerous types of game and was probably anxious to do just that in the evening or morning hours. That evening we were treated to some rice and buffalo meat supplied by local people, visited with the man who was then “Acting” Chief Nabwalya, then turned in by around 9 PM. The next day, after only a bit of commiserating with Stuart’s friends and neighbors, and some time spent in the central part of the village, near the school and government offices, I left with our graduate student colleague and made the long drive out of the valley, up the Muchinga Escarpment, through Mpika and to Kasama, the capital of Northern Province.

I recorded stories during my next visit to Nabwalya, in mid-May of 1989. I traveled with my eight-year-old son Daniel and a woman friend whose husband worked for a Canadian Aid organization at Mpika. The rains had recently abated and the road to Nabwalya had not yet been used enough to mark a trail through the tall grass. It was a very difficult trip, taking us nearly sixteen hours, including at least one rather ill-fated wrong turn, to cover less than seventy miles. We arrived at Nabwalya after 10 PM and pitched our tent under the nsaka next to Stuart Marks’s house. Stuart showed the signs of having been in the field for a long time without a break. He was thin, rather harried, and very sensitive to any discussions about his work or hunting. The pressure of living in the rather charged environment of mercurial government game guards and local friends and colleagues was clearly stressful. In Nabwalya, there were many levels of contestation, both internally and externally, regarding the livelihood of the Bisa, and it was plain to see how Stuart could find himself set in the middle of these conflicts, at least as an observer if not an outright advisor or participant.125

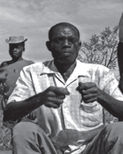

In some respects, this made my own efforts easier, since people seemed to find the recording of storytelling a rather innocuous pursuit compared to the more dramatic economic and cultural struggles involving hunting and game management. The morning after our arrival, Stuart and I spoke to a few of his friends and neighbors to arrange some recording opportunities. As we sat in Stuart’s nsaka, a young man and an older man came to visit. The older man, Mr. Laudon Ndalazi, on hearing what it was I did, asked to tell a story. I was more than happy to comply and set up my recording equipment inside the nsaka. When he sat down, the camera framed him back-lit by the bright morning light, seeping over and between the unevenly-spaced sticks tied together to make a wall of the nsaka.

Mr. Ndalazi looked to be in his early sixties, with close-cut graying hair. He was average height and slim, with an engaging smile and knowing look that was reminiscent of the American Rock ‘n’ Roll pioneer Chuck Berry. The resemblance was enhanced by the short sleeved, collared knit shirt he was wearing. He wore dark brown trousers and on his left forearm he had a thin ivory bracelet with a carved braided pattern. Mr. Ndalazi sat on a very low slung wooden lounge chair, that caused his knees to come up nearly to his chest level, and he told a lot of his story with his elbows or forearms perched on his knees.

| Bisa Storytelling 1 by Laudon Ndalazi |

To watch a video of this story follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0033.04/Bisa1

| Robert | |

| Cancel: | It’s alright mukwai, begin. |

| Laudon | |

| Ndalazi: | My name is Laudon Ndalazi. |

| RC: | Uhn humn. |

| LN: | Then I will give you a little mulumbe and nshimi, bwana. |

| RC: | Yes mukwai. |

| LN: | There’s the little mulumbe, a person kept a dog. He kept how many dog(s)? [Holds up one finger.] |

| RC: | One. |

| LN: | One. In the world there was great famine. Then that dog is the one that was catching animals for him, which he even used to leave for his children. |

| RC: | Uh humn. |

| LN: | Where he used to pass when going into the bush to hunt animals, there was one little old woman, a little old woman in the bush.126 The little old woman had a hump on her back. Do you know a hump? |

| RC: | Uhn humn. Ng’ongo, a pot.127 |

| LN: | Yes. She had a hump on her back. But he didn’t give her anything whenever he killed an animal. Whenever he killed an animal he didn’t give her anything. The little old woman was just observing. Whenever he killed an animal, he didn’t give her anything. Then one day the little old woman thought of a plan. She said, “No, this person, it is too much, he is stingy. Now, today I will also come up with a plan so that we?…128we are of the same mind.” Then he took the dog to go further. He went and found how many little animal(s)? [Holds up one finger.] |

| RC: | One. |

| LN: | One. Its name was Kamunsulu. The dog killed it. He had gone with his child. He gave it to his child to carry. He was going further. He went and found a duiker, fya! But that duiker went to pass just near?…near the green mamba, the dangerous snake…that dangerous snake so it was that little old woman who had?…who had turned into a green mamba. |

| RC: | Oh? |

| LN: | That little old woman he used to refuse to give her meat, so she turned into a mamba. |

| RC: | A snake? |

| LN: | Yes. The dog, when it came to pass, the animal passed, the dog was about to pass, paa! Right there, the dog died. And it [the mamba] even raised the?…the head. Then the person stood and said, “My child, the dog has done what? It has been caught by that…which is standing there.” “What is it?” He said, “No, it’s a green mamba. Hurry up, let’s return, it might bite us.” And then they went back?…backwards. |

| RC: | Uhn humn, to the pot?129 |

| LN: | Yes, going backwards. Then they went backwards for that old…that green mamba, that one…it returned home, that very little old woman, she went and changed again into a little old woman. And that sun did what?…it set. It set while they were there. They said, “Oh, we are going to sleep right here, you little old woman.” There that little old woman knew to say, “It’s I who’ve done that.” She said, “Oh, you sleep.” He even took that little animal they’d killed and gave it to the?…the little old woman. She cooked…ubwali and she gave them. She even showed them a bedroom130, to this side. “No, you sleep this side, with the child.” That’s how they…they slept. However, the little old woman there, where she was sleeping in her bedroom, she thought of another plan. She took that very hump that… |

| RC: | Uhm humn. |

| LN: | Yes, she took the hump and went and put it onto the child while he was sleeping, humn! The child there, she went and put it on his back and it was humn! The child hurriedly rose, “I am burnt father! I am dead father!” His father looked, he said, “Oh, sorry. My child, you are deformed. Now what shall I do? This little old woman, if I say something she will kill me.” Now, that person, then he thought, for his child to be cured of that hump…what did he think? |

| RC: | Uhm. He had to plan. |

| LN: | Yes, now what did he think? |

| RC: | Oh…? |

| LN: | Yes, it is alright mukwai. What did he think [of doing] in order to remove that hump from the back? |

| RC: | Oh…I don’t know. |

| Kabuswe C. Nabwalya [standing outside the nsaka]: No, I can’t… | |

| RC: | It’s difficult. |

| Kangwa Samson: Ah that, I can’t solve it, eh? | |

| RC: | Un huh. So it’s a mulumbe, isn’t it? |

| LN: | Yes, it’s a mulumbe. |

| RC: | Oh! It’s not a lushimi? |

| LN: | Uh uhn. Muulumbe. |

| RC: | Yah, it is just a mulumbe, really. It is very difficult. Can you explain? |

| LN: | Ah? |

| RC: | Can you explain it? |

| LN: | Ah humn. |

| RC: | Oh. |

| LN: | Yes, as it is difficult for you like that. That person thought about it also. He said, “Me, if I speak to that little old woman and say, ‘It is you who has given my child a hump,’ uh uhn, it will be an offence.” [He would be insulting her.] |

| RC: | Uhm humn. |

| LN: | “In fact, she could even kill us here.” Then he woke up to look intently at the child, like that. He thought again, he said, “Uhn humn. You, my child, stop crying. This thing, don’t think that it has…has any problem that can lead to your death, no. Now my child, we have wealth, riches, lots of it. All those friends of ours who have groceries, who are rich, those with cars, it is the hump they had looked for. Now, even us, we have good luck, we have found a hump, it has come to you. Even us, we are now going to sell it. From it we shall raise money to buy a car. |

| RC: | Oh. |

| LN: | Ahssh…The whole night, just like that, and the little old woman there was listening, there in the bedroom she…she was listening and said, “Oh no! I have given my friends wealth. So when they go they are going to sell it?” The little old woman pondered over it, she said, “Well, here things have gone wrong, my friends are going to sell it for?… (wealth).”131 Then when it was morning, that person who had a child with a hump started off and said, “No mukwai, we are going. You received us very well. We are going, we have a job of selling this thing which is on the back of my child, this…hump.” “Oh? You’re going to sell it?” He said, “Yes, since we are now rich, it is finished.” The little old woman said, “Uhn uhn, O.K.” They went, those people, they reached quite far. The little old woman was greatly troubled. Then she started off to go to…to call those people. “You, people, come back.” And these people said, “No, time is passing, we have a…a job of selling…the hump.” She said, “No, first let’s reason together.” That’s how she thought. She said the…little old woman said, “No, this hump…it is my hump. I said, ‘Let me give it to the child, perhaps it is an illness,’ but I have heard what you’ve said about it, it is true to say it’s wealth. No, friends, give (it to) me.” But this person also refused, he said, “No, I cannot give you this hump. We, we are going to sell it.” Then the little old woman also said, “No, please friends, please. Let’s, therefore, come and reason together. Me, I am bringing the hump, I will bring it right there, we go and sell it, we go and share even the money.” She then took what? That little old woman, the hump on the back there, she got hold of it and put it on her back. |

| RC: | Oh. |

| LN: | Yes, until that man said, “Let’s go my child!” And then they reached further, he said, “You see the plan I told you about. If I had said that, ‘No, it is you who…who has bewitched my child,’ the little old woman would have killed us.” That’s it, has it been understood? |

| RC: | Thank you mukwai. |

| LN: | Ehn? |

| RC: | It’s a job well done. |

Laudon Ndalazi was a confident and animated performer, without being bombastic in any way.132 His movements were fluid and economical. He had a kind of central point in his physical style, wherein he clasped his hands or held the wrist of one hand with the other in front of him, as he rested his elbows on his knees, when not using descriptive gestures. He often pointed with one hand or the other to spaces where action was taking place or to indicate areas where characters were planning to go or that they were describing. He kept referring to the hump by touching one or both hands to the rear of his shoulders, particularly when he demonstrated how the old woman removed it from her back and placed it onto the young boy. Then later he acted out her reaching over to the boy and taking the hump and returning it to her own back. One interesting set of gestures was employed to describe the poisonous snake the old woman turned into. Mr. Ndalazi held up one of his forearms, bent at the elbow with the fingers of his hand extended straight forward in a claw-like shape. This represented the snake’s head, and he showed how it followed and struck at the hunter’s dog to kill it. When both the old woman and the hunter were thinking about what course of action to follow next, Mr. Ndalazi would put a hand to his chin or the side of his jaw to indicate someone deep in thought.

When the point of the story reached the dilemma of how to cure the boy’s condition, Mr. Ndalazi stopped and asked first me then, Stuart’s friend and associate Kangwa Sampson, how the hunter should proceed. He sat forward in the chair, forearms on knees, and looked expectantly at one of us then the other, while smiling as if he held secret knowledge. When neither of us could offer a course of action, Mr. Ndalazi went on with the story, answering my request for an explanation by saying, “Yes, as it is difficult for you like that. That person thought about it also.” When he ended the story, he leaned back contentedly, and received our praise for a story well told and cleverly explained.

Years after this session, Stuart Marks mentioned two things that emphasized the importance of performance context in any storytelling event. First, denying meat to the old woman was a powerful social statement of disconnection or estrangement, since the sharing of game meat is a crucial act of solidarity between relatives and allies. The fact that the hunter passed her place regularly on his way to and from the bush without offering her meat suggested an obvious and intentional slight. Second, and here is a good example of how knowing the area and people where you record narratives can be crucial, there apparently actually was an old woman in the village who was a relative of the chief and who was quite unpopular for having a combative disposition, never sharing and demanding things from her neighbors. She also happened to have a hunched back. Mr. Ndalazi was pretty clearly injecting this local dimension into his tale, something that can be a common practice in intimate or even public events.

After I replayed the audiocassette of this performance, Mr. Ndalazi wanted to tell another story, so I set up and began to tape again. He began slowly, saying he had a small mulumbe to impart, and held his left hand, elbow on knee, to the side of his forehead as he thought about what he wanted to say.

| Bisa Storytelling 2 by Laudon Ndalazi |

To watch a video of this story follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0033.04/Bisa2

| Robert | |

| Cancel: | Let’s begin mukwai. |

| Laudon | Here is a little mulumbe, friend, this little one, Bwana.133 |

| Ndalazi: | A person had seven children, he bore seven children. Of the seven children, these two went to join the army to work. These other four were to travel with him, wherever you went even these four children set out. This other one was to sweep where you…if you soil yourself, yes, now he is sweeping that, yes. Then of the four children, this one, these other two are workers in the army, these other four were to travel with him, this other one was to wipe “dirt” from his father, yes. Now of these things, what was it Bwana? |

| RC: | Ee, I don’t know. |

| LN: | Ask Mr. Marks. |

| RC: | Uhmmn? |

| LN: | You ask Mr. Marks, you ask Marks. Let him come and listen to this. |

| RC: | Ooh. Mr. Marks, Mr. Marks. Mr. Marks come here! [Stuart walks over from outside his house to the nsaka.] |

| Stuart | |

| Marks: | Yes? |

| RC: | Come. He’s posed a mulumbe. |

| LN: | We’ve told a mulumbe to this one, this one’s failed to explain what it means. I have said a person bore seven children. Of the seven children, two went and found a job in the army. These other four were to travel with him, where you go even the four children have to go. This other one was to wipe dirt wherever you sat. Which of these children would you choose as the truthful child? A trustworthy child? |

| SM: | He’s giving you a riddle, eh? |

| RC: | Uh hunhm. |

| SM: | Can you figure it out? |

| RC: | No. |

| SM: | Do you know it? |

| RC: | I don’t know it. |

| SM: | Me too, I’ve failed [to understand it]. |

| LN: | The child you would choose from these, these who have joined the army, and these you are traveling with they are four, and that one who is wiping “dirt”? Of these children which one is trustworthy? |

| SM: | Let’s hear mukwai, let’s hear. |

| LN: | Oh. Of the seven children, the truthful one, you know how a buffalo is, don’t you? The buffalo, you know it? |

| RC: | Yes, the buffalo. |

| LN: | It has how many feet? |

| SM: | Four. |

| LN: | Four (folo). It sets out saying, “Let me drink water,” all the four feet go there, all four. |

| RC: | Oh, the feet. |

| LN: | Yes, all the four feet go there. Then that tail, when the buffalo shits, what does it do? It wipes it. Then those two horns, if you…it has the urge to kill you, those will become army workers (soldiers). Now they are to kill you. Yes, that’s it. Aahha. Thank you. |

| Audience: | Good job. |

As in the previous tale, Mr. Ndalazi is interested in testing his audience’s perspicacity when it comes to solving dilemmas or conundrums. When he first sets out the situation for me, he speaks slowly and enumerates the various numbers of “children” on the fingers of his left hand, touching them with the fingers of his right as he describes each set. As is the case in riddles or metaphors, Mr. Ndalazi does not refer to the actual animal or its body parts but instead builds up a description, this wasn’t really a “story,” of what each individual or set of children did: two soldiers, four others who followed them, and “a sweeper.” He acts out the four walking along as well as the sweeper, cleaning up behind the four. This last mime was enacted with his right hand reaching behind him and swatting back and forth behind his seated buttocks. As in the earlier performance, he leaned forward to ask me the answer and, when I said I did not know, he pointed to Stuart, who was nearby, and insisted I call him over to see if he could solve the conundrum. He then went through similar gestures to set out the problem again and, when neither of us even ventured a guess, he used his hands to set out the answer in the way he described the various parts of the buffalo’s body. He framed the question of the puzzle in an awkward way, asking initially, “Now of these things, what was it Bwana?” Then he asked Stuart, “Which of these children would you choose as the truthful child? A trustworthy child?” The first question was most relevant to the conundrum’s structure, though in the end, the answer he provided clarified what he was looking for from his audience. The question of choosing one of the three groupings over the other, ascertaining who was the most “trustworthy,” seems not to belong directly to the question actually being posed. It served more as a kind of generic entry into the necessity to sort out the data and choose. In actuality, the question was linked to discerning the metaphorical—perhaps metonymical is the more appropriate trope—sum of the parts that added up to being a buffalo. The reference to children might have been an allusion to the way young people often entertain themselves with riddle competitions or stories. Again, Mr. Ndalazi seemed delighted with himself and sat back in his chair, saying “Thank you,” in English. A young boy who sat next to me said to him, “Good job.”

The overweening sense of this session was Mr. Ndalazi’s desire to both show off and impart his knowledge. He performed mulumbe tales that set forth two different kinds of conundrums. The first was a rather involved narrative that focused on the clever ruse employed by the hunter to rid his child of the unsightly hump given him by the magical old woman. Asking his listeners for a solution to the problem was, unless they were familiar with that particular tale, pretty much rhetorical. It would have been almost impossible to “guess” the answer. The second performance was much less a narrative than an extended riddle, a bit like the classic posed by the Sphinx to Oedipus: what walks on four legs in the morning, two legs in the afternoon and three at night? In this case, the figuration involved a buffalo and some of its body parts. It may have been possible for a local audience to figure out the answer or to simply recognize the riddle as something that had been posed on other occasions. Stuart and I had not heard this one before and were impelled to ask Mr. Ndalazi to supply the answer. He clearly enjoyed his role as a teacher, or maybe just someone who had the chance to showcase his cleverness in a context he could control. It was also evident that the context of his two milumbe was embedded in the local environment of hunting, social/familial relationships, especially those involved in sharing game meat, and the knowledge of animals and their characteristics.

We sat a bit longer, chatting, and eventually I set out for the primary school, where some of the students had been recruited to tell stories by one of their teachers, Mr. Elvis Kampamba. Elvis had ended up in our vehicle the evening before, volunteering to guide us to Nabwalya after encountering us while passing in another Land Rover owned by the Integrated Rural Development Project office at Mpika. Having someone who actually knew the road made the last six or seven miles of our trip much easier. We also had the opportunity to get to know a bit about Mr. Kampamba and his work as a schoolteacher in this rural, isolated venue. We walked to the somewhat dilapidated school building, which was scheduled for replacement by the proposed new structure discussed at the meeting I attended back in October, and set up a camera and a chair for the performers just outside the classroom. I recorded five young storytellers and then we were interrupted by rain. The rainfall was heavy enough to cause us to seek shelter in a section of the schoolhouse that did not leak, which turned out to be a bit of a challenge.

When the rain let up, we returned to Stuart’s place. Stuart’s colleague, Kangwa Samson, told me that he’d arranged something for the next day on the other side of the village. In the morning Kangwa guided me, my son Daniel, and our friend Marie to our destination. We walked along the Munyamadzi River and paused for a while to take some video of the crocodiles sunning themselves in the sand on the opposite bank and of the sizeable group of hippos entering and settling into the river. We eventually reached the section called “Chibale’s Village,” where Kangwa’s mother lived and where a large group of men and some women, numbering around fifty, had gathered at a house to drink beer. The occasion was actually supposed to conclude the cooperative harvesting of a resident’s sorghum farm, but the rains from the day before had made it impossible to properly gather the harvest. Since the beer drink had been arranged as payment for labor, and the beer had already been brewed, the group came together to consume its compensation before actually carrying out the work. When we arrived, a man was going around writing down the names of those who were there so that they could later be recalled to carry out the harvest. The groups gathered within and around a small nsaka, talking, laughing and drinking beer from at least one large clay pot. The beer was a kind of katubi, in this instance, a sorghum-based brew that was heated over a fire and, because of thick sediment that floats at the top, must be drunk through a straw poked down below the surface in order to sip the warm fluid underneath.

Kangwa did most of the talking when we arrived, and I set up my camera and gear in front of a house next to where the drinking was going on. A low, flat wooden stool served as the performers’ perch, with open land forming the background of the camera’s frame. A few men came by to talk to me, and I also contributed some money to keep the beer flowing at the party. Eventually, I got a volunteer to tell the first story, in front of an audience that seemed to be dividing its time between observing the performances and going next door for more beer.

George Mwampatisha134 was in his mid thirties, he wore a heavy dark brown sweater, with the sleeves pushed up at the forearms. His trousers were dark gray with light tan square patches sewn over each knee. This informal dress style suggested that he, like most of the men at this gathering, had come dressed to work in the fields. Sitting on the low stool, with his knees just above waist level, Mr. Mwampatisha was not an overly demonstrative performer, taking on a rather serious mien and mostly employing subtle gestures as he began his story.

| Bisa Storytelling 3 by George Mwampatisha |

To watch a video of this story follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0033.04/Bisa3

| GM: | George Mwampatisha |

| Robert | |

| Cancel: | Begin. |

| GM: | There was a little thing. People lived…Listen thoroughly, children? Uhm hrghm. I am George Mwampatisha, listen attentively. People started off on a journey into the bush. A man and a woman. Then they walked into the bush to hunt animals.135 They walked, they walked, they walked, they walked. They found nothing, there were no animals in sight. Aah! Right there, when they walked like that, when they passed through the bush, they walked, they walked. They were tired. And heavy rain came…very, very heavy rain. It rained heavily on them.136 They were terribly soaked by the rain, now they felt very cold. They even became very tired.137 Yaah! Then they saw a plume of smoke in the bush: futu, futu, futu, futu, futu…yaah! “What’s that?” “Let’s go there.” When they arrived there they found people were seated. “Hello there mukwai!” “Come in. Who are you?” They said, “Hello, it’s us.” “What is the matter?” They said, “No mukwai, we went into the bush (to hunt) but animals are nowhere to be seen. Now we are feeling very cold, we are very tired.138 Now we wanted to go to people in the village.” Then they found lions seated in the bush.139 |

| RC: | How many lions? |

| GM: | Two. |

| RC: | Oh. |

| GM: | And there was one cub. |

| RC: | Uhn humn. |

| GM: | Then right there now, certainly. They said, “Sit here.” Then the lion responded and said, “Yah. It’s very good. Yah! I have been agonizing about what to eat. Now food has come near.” “Certainly, you man, it’s good fortune that you’ve come here. Today you will see what I am going to do to you.” Now as they sat, the man said (to himself), “Yah! Yes, this is truly a lion. It’s very fierce. Now what am I going to do?” Then there arose something in the bush that said, “No, you, you…you should be very brave. They eat you and I also eat them. They eat you and I also eat them. They eat you and I also eat them.” The lion said, “Oh. Is that so? My child, go. But because you are foolish do come back, because you are foolish do come back.” The child (lion cub) left right away. He didn’t come back. She sent another cub. She said, “Well, because you are foolish do come back”, he also went. Then from there, that’s how all of them rose and set off, running. Ubulubulubu! She said, “Yes, heh! Things are bad, yes!” That’s how they went, those people. Yes, mukwai, yes. [Mr. Mwampatisha rises up as he ululates the ideophone and as he speaks the last words of the story he dances and turns in a circle before walking away, causing the audience to laugh loudly at the dramatic and abrupt ending of the performance.] |

George Mwampatisha began the performance with his hands clasped in front of him and his forearms on his knees. As he began he told the children in front and to his right to listen closely to the story. He might have initially been a bit nervous, as he gave his name a second time and told the children again to listen to him. When he began the narrative, he enumerated things on his left fingers, indicating them with his right, “People started off on a journey…a man and a woman…” He told a lot of the story using his left hand to indicate actions or resting his left hand on the side of his face as he described something. He’d also return to clasping his hands in front of him for relatively long sections of the narrative. Early on, when he uses an ideophone to describe the smoke rising from the shelter in the bush, he holds his left hand over his mouth to slightly distort the sound of “futu, futu…” Then he returns his forearms to his knees and grasps his right wrist with his left hand for a fairly long descriptive section, until the couple gets to the part of their explanation when they said “…we are very tired.” He briefly spreads his hands to say “Then they found lions seated in the bush.” Then there’s another long period of speaking with his hands clasped. As each lion cub wanders away, Mr. Mwampatisha sweeps his right palm over his left to indicate movement and finality. After doing this several times, he narrates the final part of the story where in the confusion the humans rise up, ululating, turning in a circle and making their escape. He also walks off himself, saying, “That’s how they went, those people. Yes mukwai, yes.” The audience was clearly delighted by this last piece of dramaturgy and laughed and applauded the performance.

There seemed to be no great thematic point made in this tale. The man and woman who’d wandered in the bush only to find themselves among lions did not seem particularly resourceful and there seemed no other themes being played out in the encounter. Mr. Mwampatisha did not provide a lot of details to contextualize the narrative’s plot development.140 The couple, who are stranded in the bush and come upon a “village” of lions, seemed doomed until a voice begins to inform them that “They eat you but I also eat them.” The voice is threatening enough to cause the lion adults to direct their cubs and, indeed, themselves, to surreptitiously but quickly leave the scene. At the point where the adult lions seemed poised to also disappear into the bush, the humans were able to jump up, making noise and dancing, and escape from the situation. The denouement of the narrative was rather vague, though Mr. Mwampatisha’s dramatic flourish at the end was very pleasing to his audience. If a theme is to be identified, it is probably that the lions were frightened off by a terrible, boasting voice that confidently predicted it would devour them. In other versions of this tale, part of the point is to indicate that the voice frightening the lions belongs to a much smaller animal. The point seems to be that the lions were too easily intimidated by words alone. The overall context of encountering animals in the bush, as well as being unnecessarily put off simply by verbal threats, was an example of using everyday concerns as the backdrop to a narrative performance. Dangerous wild animals are much less common in other parts of rural Zambia than they are in the Luangwa Valley, and most likely lose their immediate connotations in the former environments.141

The next performer was a guitar player, identifying himself as “Johnny Walker,”142 or, rather, some audience members supplied that name and he concurred with them. Mr. “Walker” was a relatively young man, probably in his mid twenties, who was dressed in a gray long sleeved collared knit shirt, with black and white horizontal stripes. He wore dark gray trousers with the cuffs rolled half way up his calves, again suggesting his readiness to help in the labor of harvesting sorghum. His guitar was most likely locally made, with a weathered rough-hewn neck and fret board, metal strings and an acoustic body with the top painted flat green. Mr. “Walker” played a rather long introduction, which inspired a man tending a fire just to his right and rear, to stand up and begin dancing in time to the music. An audience member encouraged the musician to sing. Instead, he stopped playing and gave the introductory formula to begin a story, “Patile akantu, ine …” [There was a little thing, I…] but after five or six words he stopped and went back to playing. The man behind him continued dancing while someone behind me in the audience began to sing softly to the music.

Another man in the audience told him not to sing. Soon thereafter, Johnny Walker stopped playing, stood and walked away.

At this point I was feeling particularly awkward, wondering if performers were simply going to put in a token effort then persist in cutting me off as they walked away from the camera. Eventually I would realize that the performers simply thought they were supposed to end their efforts, by getting up and walking away. Nevertheless, people were neither overly friendly nor particularly interested in talking to me about who I was and what it was I did. While not openly hostile, the reception was certainly ranging from lukewarm to indifferent. Eventually, the man who’d been recording everyone’s names in a large notebook sat down to tell a story.

Lenox Paimolo143 was still holding the pen in his hand as he told the narrative, having placed the notebook down on the ground.

| Bisa Storytelling 4 by Lenox Paimolo |

To watch a video of this story follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0033.04/Bisa4

Lenox Paimolo looked to be a man in his mid to late thirties, stockily built and with thin, trimmed mustache and goatee. He wore a short-sleeved grey, collared shirt, with the sleeves rolled up a bit over his biceps, and olive-colored trousers, rolled up to just below his knees, again, as with some of the other performers, indicating he had come dressed to work. He held a pen in his right hand as he told the story, and wore a baseball cap with a red brim, blue mesh top, and a white front piece that had the name “Randy” printed on it. On his left wrist, he had a metal-band watch.

Mr. Paimolo was a confident and animated performer. He had a strong voice and moved the story along quickly. One of his most common gestures was enumerating the three main characters, counting the fingers on his left hand with his right. He did this each time he compared the characters or asked the audience to decide which the most important figure of the three was. He mimed shooting a rifle, cutting up meat, and, particularly, hoeing. He kept his focus despite a steady din from the place where beer was being consumed and even among the people watching his efforts. Behind him, several boys walked into and out of the frame, trying to strike poses for the camera. Another man, smoking a cigarette and mostly following the story, left the frame to find a light for his cigarette, then returned to mime reactions to the tale’s events and even applauded Mr. Paimolo at the end of the narrative.

His mulumbe struck an interesting chord in the context of Nabwalya’s economic life. While cultivation is a constant of the village, hunting is its more glamorous and prestigious activity. Directly comparing farming with hunting and simply having money in your pocket is to get to a core concern, how to best maintain a level of food security in difficult times—the difficulties stemming from both natural impediments to growing crops and official impediments to hunting game. The farming emphasis also seemed relevant to the purpose of the gathering, and perhaps undergirded the obligation the beer drinking participants were being held to when it came time to bring in the delayed harvest. Overall, the sense of farming as a stable practice is the mulumbe’s main theme, a reminder that diversification was a crucial alternative to relying only on hunting for sustenance. Mr. Paimolo’s theme might be somewhat contrived, since farming in the mid-Luangwa valley has always been difficult to carry out with any kind of regularity. Most good soil is found near the rivers, but these are subject to the twin plagues of flooding and drought. Further, the many animals in the area, often moving in the direction of the river for water, are always a threat to graze in people’s gardens. As is the case with many narratives, links to actual practices or conditions may or may not be relevant to any particular tale, with symbolic or allegorical themes often taking precedence.

After a brief interlude that allowed me to videotape a bit of the beer drink and sample some for myself, the next performer, Mr. George Iyambe144, who looked to be in his mid or late twenties, told a fairly long story, with a song in it and a good deal of audience participation. Mr. Iyambe sat on a long log, with two colleagues on either side of him. One was the guitar-playing “Johnny Walker,” and the other a stocky man wearing a thick sweater with sleeves pushed up over his elbows, the collar of his plaid shirt stuck out of the crewneck, and tan trousers with the cuffs rolled up over his calves. He also wore a pink “groundskeeper” cap. Mr. Iyambe wore a tan long sleeved collared knit shirt, with horizontal stripes, over another collared green cotton shirt. His trousers were dark green and someone handed him a baseball cap to wear during his performance. He fooled with the plastic fastener at the back of the cap while I was waiting for him to give his name before beginning. He placed the cap on his head as he started the story, but the fastener did not hold and the cap remained rather large and loose during his performance. This, along with the fact that he was missing his right upper front tooth, gave him a comical visage as he narrated the tale.

| Bisa Storytelling 5 by George Iyambe |

To watch a video of this story follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0033.04/Bisa5

George Iyambe began the narrative with his elbows resting on his knees and arms crossed holding his biceps. He spoke in a loud voice, partly because the audience was a bit restive and rowdy, and emphasized his words by periodically jutting his head and shoulders forward. Early in the narrative he explained how in times past people carried babies around in slings made from animal hides, gesturing with both hands to emphasize how the skins were made and put onto mothers’ backs. He also leaned forward when voicing the husband’s argument against having to kill a lion to make a sling for the baby. In part, his performance posture was due to the long bill of the cap covering his eyes, so Mr. Iyambe had to lean forward and tilt his head up in order to make eye contact with the camera and his audience. Before the husband sets out on the hunt, Mr. Iyambe acts out loading the gun with ball and shot and tamping it down with a metal rod, using his left hand to hold the imaginary barrel and his right to repeatedly push down the load. He also used the formula of asking how many bullets and holding up two fingers, as I answered two. He then acted out a lot of the activity of going into the bush, spotting the lion, staring at it and aiming the gun. Within these activities, he touches the arm of “Johnny Walker,” to his right, as if he were the hunter grabbing the young nephew’s arm to say, “Ah…we must go back home…” When he acts out the lion disdainfully taunting the hunter before he kills him, he draws some laughter from the audience. He also combines a verb and ideophone (“Bwa!”) to describe the lion killing the hunter, and acts this out by twice slapping the side of his left fist with his right palm, making as if to throw down the victim each time. He gestured emphatically to show the young boy escaping the lion and returning to recover what was left of his uncle. Then Mr. Iyambe crossed his arms over his thighs and leaned forward to sing the song. There was loud and enthusiastic singing of the chorus by the audience members and his two colleagues seated on either side of him. Near the end of the first rendition, a man and woman came behind them and danced to the song. He gesticulated broadly to describe the boy’s movement over three days towards his village, then began to sing again, with the same level of response from his audience and the two dancing behind him. Before the next and final rendition of the song, George Iyambe broadly acted out the movement of the boy, pointing to the places he was going and portraying the reaction of people hearing his song in the village. During the singing of the song, he kept his forearms on his thighs and hands crossed at the wrists between his knees. He leaned so far forward that his hands were near his face, with knees up to his chin. He also moved his head and body rhythmically to the singing. The story’s ending was spoken in an even louder voice and he jumped up and walked away at its conclusion, drawing loud applause and appreciative remarks from the audience.

Thematically, this performance clearly focuses on marital relationships and how these can be damaged by unreasonable expectations. The inclusion of a song marks the tale as a lushimi, one with a thematic explanation at the end. Mr. Iyambe takes time to detail the practice of making slings from animal hides to carry infants. He contextualizes this practice by reminding his audience that these days cloth is used for the same function. As in Mr. Mwampatisha’s earlier story, a lion is encountered in the bush and, this time, the lion kills the human who has intruded in his realm. While the theme of an arrogant and unreasonable wife is at the forefront of the story’s development, there is another important familial relationship developed here as well. The young nephew, who’d accompanied the hunter on the journey, would play a major role in moving the narrative to its just resolution. He returns to gather his uncle’s remains, then finds his way back to the village while singing the incriminating song that alludes to what had transpired. Further, he is welcomed back by the people of the village, who then become the arbiters of justice when accounting for the hunter’s death and his wife’s part in it. The narrative role played by both the hunter and his nephew serves to move the story along to its conclusion but also, on a more realistic level, parallels actual matrilineal relationships between accomplished older hunters and their younger protegees, who are often maternal nephews.145 This familial relationship in the end trumps the marital bond, with a clear misogynistic caution about women’s unreasonable demands.

Mr. Paul Chandalube followed, with a story featuring Kalulu, the trickster hare.

| Bisa Storytelling 6 by Paul Chandalube |

To watch a video of this story follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0033.04/Bisa6

| Robert | Wait…we can begin. Give me |

| Cancel: | your name. |

| PC: | Paul Chandalube. |

| RC: | O.K. Begin mukwai. |

| PC: | I am going to talk about the respect of animals, or how big the animals are. Who is the king of animals? Then it was Kalulu who said, “I am the king, mukwai.” |

| RC: | Uhm humn. |

| PC: | Then there were animals such as the elephant, the buffalo, the zebra, all the animals. Hare was there, even Hippopotamus. They said, “We are the kings.” The clever Kalulu spoke right there. He said, “Are you the king?” They said, “Yes.” Hare said, “Well, all of you animals, would you say you are greater than I?” They said, “What insolence! This fellow, how can you ask whether or not we are greater than you when you are so small?” Kalulu said, “Well, you Elephant and Hippopotamus, can you defeat me in a tug-of-war contest?” They said, “What nerve! Try and you will see. We can pull you, draw you over the center line and even throw you away.” He said, “O.K. It’s alright. We can make a?…a rope. Let’s go and strip bark-rope.” |

| They went and stripped bark-rope and made a very long rope. He [Hare] said, “My Lord!” His honor the Elephant said, “Yes?” “Can you defeat me in a tug-of-war contest?” Elephant said, “Argh! You, Kalulu, you are so tiny.” Kalulu said, “Let’s go and try.” He took the rope that was properly made, made a loop and fastened it around Elephant’s neck. He pulled slightly and said, “Stand right here. I will come back again. I am also going to fasten the rope around my neck so that we can begin pulling.” He went to Hippopotamus and said, “Hippopotamus!” “Yes?” Kalulu said, “Giant Hippo146, can you defeat me in a tug-of-war contest?” Hippopotamus said, “Nnaah! You think, me…Kalulu, you think I can fail to do that?” Kalulu said, “O.K. Come here.” | |

| Then he [hippopotamus] came out [of the water]. Hare thought, “Let me do what, now?” He made another loop and fastened it around the hippopotamus’ neck. He said, “O.K. I am also going to that side. Right when I pull, both of us should begin to pull.” Then he went to a shrub somewhere there, got a big stick and hit the rope. Nku, nku. Yah! Elephant at the other end of the rope said, “Damn it! It’s now time to pull each other.” At the other end of the rope, where Hippopotamus was at the river, he said, “Kalulu said, ‘Let’s pull each other.’ Mmpph!” “You have begun to pull each other mukwai.” Kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe-kwe. | |

| Elephant on the other side pulled hard. He pulled hard again. He said, “Well. Ahrgh! Auurgh!” Hippopotamus on the other side of the rope also pulled. “Ubruu urruuru!” They met at the center-line. Then Kalulu said, “You are the ones who said, ‘We are the greatest.’ I am the greatest of all the other animals.” That’s what Kalulu…that’s what Kalulu said, “I am the greatest of all the other animals mukwai. All of you…you are very small. Have you seen the way you have treated each other?” | |

| That’s it mukwai. This is where I end. It is a short one [story]. |

Mr. Chandalube147 was in his late early forties, wearing a white short sleeved collared shirt with thin gray lines in a grid pattern. He also wore light brown trousers. His clothes seemed newer and perhaps more expensive than those of the other performers. It’s likely that he had not come to help with the harvesting of the crop. He had a rather deep voice and a serious, no-nonsense style of speaking. He began his narrative sitting straight up with his elbows on his thighs and left hand holding his right wrist. As he briefly identified animals that might vie for the title of the greatest or most powerful, he enumerated them on his left hand, using his right to touch each finger as he named them. He then bent low and touched the ground next to him with his right hand to indicate where Kalulu ranked in this hierarchy. He returned to holding his wrist as he spoke, until he acted out the initial interaction and challenge Kalulu makes to the larger animals. There’s a bit of pointing at each other as they speak, then he used his left hand to act out Elephant and Hippo feigning grabbing Kalulu and tossing him to the side. He then mimes the making of a rope, and playing out the thick rope along the ground. Mr. Chandalube acts out the looping of the rope around the Elephant’s neck by using his hands to indicate the shape of the noose and then moving them up to and behind his own head. Acting as Kalulu, he tells the Elephant to wait and gestures to how he’s going to grab the end of the rope, which is out of sight. When he depicts the Hippo engaging the noose, he actually shapes it in front of him then acts out looping it around its neck while holding his hands out in front, as if he was placing it over the animal’s head. Describing how Kalulu goes to a mid point between the competitors and bangs on the thick rope with a large stick, Mr. Chandalube points in front of him to show where the Elephant took up the challenge and began to pull, then points behind him to show where the Hippo was similarly engaged. Instead of acting out animals tugging on a rope, his description of the contest actually focused more on the long and loud ideophone, “Kwe-kwe-kwe…” whereby, elbow and forearm parallel to the ground, he rapidly moved his left hand, palm down, and forearm back and forth to indicate how the animals struggled to gain the advantage. When he ended by saying Kalulu had won, he again touches the ground with his right hand to emphasize the trickster’s small stature. Paul Chandalube spoke more loudly and rapidly as he ended the performance, standing up and walking away as the others had done.

This is a rather well known trickster narrative. I recorded a version that was very similar to this one when I visited the Lunda area later in the year.148 Like many trickster stories, the plot revolves around using cleverness to defeat sheer size or strength. This particular performance, however, is at least partly shaped by the context of the narratives that came before it, so that the theme of animals and the bush again underlies the tale’s machinations. The trickster hare, in this case, is like the hunter who must overcome large and dangerous animals. He is very similar to the clever hunter, in the session the day before, who had to find a way to get the evil but dangerous old woman to somehow remove the disfiguring hump from his son’s body. He is like the clever nephew who chose to sing a falsely festive song to allude to the evil done his uncle by the wife. A central concern of this and other narratives I recorded treats the problems of greed and recklessness in a hostile environment. Mostly, animals are the danger here, but there is also the sense of potential danger from other, sometimes human and usually female, forces as well.

At this point, people were increasingly boisterous and obviously having a good time, but pretty much disinterested in the prospects of more performances. I thanked a few people nearby and let Kangwa know I was done. We said our good byes and walked back to Stuart’s through another section of the village. Kangwa wanted me to see various things, like a house being built and sorghum drying on bamboo mats, etc. I photographed or shot video of some of these objects or practices as we paused at each location. We reached Stuart’s place in time for some lunch.

Later that afternoon, I recorded three more stories at Stuart’s nsaka: two from Kabuswe C. Nabwalya, the man who was working on a building project for Stuart and who had comprised part of the audience for Laudon Ndalazi’s performances the day before, and a third from a young boy named Peter Chisanga Tembo, who was acting as a game-counter and assistant for Stuart.

I want to focus on only one of those stories, a brief mulumbe, told by Mr. Nabwalya.

| Bisa Storytelling 7 by Kabuswe C. Nabwalya |

To watch a video of this story follow this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0033.04/Bisa7

Mr. Nabwalya149 was in his late twenties or early thirties, sitting back on a lounge chair slung with an animal hide to comfortably support his weight. He wore a green or khaki long sleeved cotton shirt, rolled up to his elbows and fastened with only one button below his chest, with the shirt tails knotted at his waist and a pair of light brown trousers. He’d been working on Stuart’s nsaka both days we were in the village. Stuart later told me that Mr. Nabwalya was a son of the late chief and that he had somehow managed to visit Mpika and run up some bills in Stuart’s name. The labor on the nsaka and some other chores around the place were his way of repaying the money. He told this brief narrative with minimal gestures, mostly resting his wrists or hands on his upper thighs. When he enumerated the four points of the mulumbe, he marked the first two by lifting his left index finger to signal first “one,” then “two” of the points, but did not use his hands to signify the other two ideas. While explaining the answer, he alternated between subtly lifting one hand and the other to emphasize the father’s commentary.

Looking over this very brief, allusive rather than specific mulumbe, it is notable that the social concerns set out by Mr. Nabwalya resonate with most of the narratives recorded in this village. Marrying a good woman is a concern, while at the same time he advises the audience not to trust women with secrets. This in part touches on the theme of Mr. Iyambe’s story about the greedy wife. His other two points about distrusting the government and being suspicious of frequent visitors, even if they are ostensibly “friends,” speaks to wider social concerns but also to the specific tensions of living in Nabwalya, at the center of the contestations between local cultural and economic imperatives and the efforts of government agencies to curtail the key activity of hunting. As mentioned earlier, one of the strategies taken by at least one agency was to appoint local young men as game scouts, thereby giving them a stake in enforcement of game laws. But these young men also became objects of distrust by local people, who were even more wary and secretive when it came to hunting activities. Hence the further relevance of points two and three in the mulumbe.

A few years after this visit to Nabwalya, I corresponded with Stuart Marks regarding my initial reading of barely suppressed hostility or discomfort and distance emanating from even the men who agreed to perform narratives for me. Stuart responded with a detailed letter that drew from both his memory and field notes. I quote one particularly salient passage:

You are right about the stresses and strains of fieldwork. The isolation of the rainy season was coming to an abrupt halt and it was difficult to know what visitors each new day would bring. The previous week had brought two Land Rovers full of game guards and wildlife scouts to search for a “poacher’s lair” that had been spotted near Nabwalya from Owens’ aircraft.150 The scouts had not gone far into the bush across the Munyamadzi River and had not been very diligent in pursuing the “poachers,” who in any case had already received word of the scouts’ arrival. So the scouts had spent the rest of their time hanging around and harassing villagers. (personal correspondence)

This is only one example of the kinds of “visitors” who would drop in on Nabwalya’s residents, mostly without warning. Almost all of the visitors had some relationship to game management agencies or conservation groups—or even just tourists or safari hunters hoping to observe an “authentic” rural village—who were usually more interested in animal than human welfare. Stuart even conjectured that the inordinate amount of time we’d spent videotaping the crocodiles and hippos in the river might have been seen by residents as yet another example of skewed priorities. It is therefore not surprising that people were not forthcoming with long and involved narrative performances, taking time out of their lives for relatively meager returns. This is an attitude that applies in most of the places I visited in the hope of recording performances, but it is manifestly most understandable and observable in a living situation as precarious as was the one in Nabwalya. Even the giving of their names by performers was a rather problematic choice, with “Johnny Walker” being the most obvious example of someone who did not want to be pinned down or identified later on, by me or more likely some representative of authority and game management. In general, people everywhere I went in rural Zambia may have been initially uncomfortable having me record their names on audio or videotape, but conditions were usually rather low key and after some explanation most performers accurately identified themselves.

It really was unusual in the places I’ve gathered oral traditions for there to be such an obvious overlap or literal parallel between the imaginary world of storytelling performances and the real life conditions of performers and their audience. Chief Nabwalya himself, Mr. Blackson Somo, had only recently been appointed, and even then under the tentative “Acting Chief” title, after a lengthy succession dispute, which led to even more instability and uncertainty in the village’s socio-political relationships.151 The position of chief in this polity was complicated by his interactions with outside agencies looking to provide material and economic opportunities to residents in order to offset profits previously made from hunting. The chief is often the main go-between in such negotiations and exchanges, and he is bound to spread the wealth to colleagues and others who will strengthen his social position. This sometimes means that not everyone in the community will share in this wealth, and this means that those who are not included in these benefits have little incentive to stop hunting. In any event, it is safe to conjecture that the performances I recorded and information I gathered were always passing through the filter of caution and suspicion that characterized the village’s relationship to outsiders.

After this second day of collecting narratives, we settled in for the evening and, the next morning, led by Stuart and Kangwa we made a speedy return trip through the valley and up the escarpment to Mpika then Kasama. In an effort at reciprocity, I would then guide them to the village of Nsama, in the Tabwa area, where they consulted with local hunters about their beliefs and practices.

Postscript

Near the end of September 2005 I met Kangwa Samson at the government rest house in Mpika, Northern Province. Because I was traveling by public transportation, mostly buses, given the time and expense such a trip would entail it was not possible to make the long arduous journey to Nabwalya. Additionally, it was the hot season and the Valley was particularly inhospitable for travelers. I’d sent a letter to the Valley when I arrived in Zambia in late August, and hoped that Kangwa had received it so that we could meet. The first evening at the rest house, as I sat at a table in the lounge having a meal, there was a knock on the door and I answered it to find a very slim, bedraggled older man. I called the guesthouse’s manager to greet the visitor then went back to my meal. The visitor was asking the manager about Dr. Cancel, and it was only then I realized that it was Kangwa Samson. Neither one of us had recognized the other, both having aged noticeably in the intervening sixteen years since we’d last seen one another.

We greeted each other warmly then he sat down to share my meal and catch me up on his journey. Kangwa was now headman of Mbuluma village some distance from Nabwalya and supported two wives and their nine children. One family lived with him and the other in a distant village. Mr. Samson brought greetings from Elvis Kampamba, who is now the headmaster at the primary school in Nabwalya. Kangwa had walked two and a half days through the scorching heat of the Valley, stopping at a village one night then simply sleeping in the bush the second night, to make our rendezvous. There’d been several years of drought which more or less decimated the crops and any grain and vegetable surplus in the area. Moreover, hunting enforcement was more stringent than ever and people mostly did not hunt with guns anymore. If anything, they set snares and pit traps to catch game, which was less noticeable to game management authorities. Elephants had, in fact, made a come back in the Valley. So much so that they were in some instances eating the meager attempts at growing crops by villagers and even beginning to destroy crucial sources of food by damaging mango and other fruit trees. He said that in the last five months two people had been killed by elephants. Kangwa claimed there was out and out famine in the Valley and promised food relief in the form of flour to make the staple starch ubwali had been slow in coming. By around 9 PM, we agreed to meet the next morning in my room in order to do some work, and Kangwa left to find a relative in town he planned to stay with.

At around 8:30 AM, Kangwa came by and we proceeded to watch the video record of Bisa performances on DVD. Our pattern, as it emerged, was to watch each performance, discuss possible themes of the stories, and, mostly, fill in biographical information on the storytellers. Most of this information has been worked into the footnotes of this chapter. Clearly, I am relying here on Kangwa Samson’s knowledge and impressions, which is not the same thing as gathering similar information from the performers themselves or their families. However, in his years as a friend and research associate of Stuart Marks, and in the time I knew him back in 1988–89, Kangwa has proven to be very reliable in his impressions, observations, and gathering of data. Moreover, he had arranged and witnessed the original session, in his mother’s section of Nabwalya, which is the central focus of this chapter, and knew most of the performers and audience members fairly well. Be that as it may, even in the few instances where I was able to speak directly to performers or their relatives, it’s best to remember that biographical or autobiographical material is always passing through filters of time and/or intent.

When it came to evaluating the tale by George Mwampatisha [aka George Kalikeka], Kangwa Samson offered what he felt was a clearer, more common version of the story. In some ways, this story is actually quite different, but it retains the central section of the lion and his family being scared off by the threatening voice of a smaller animal. Kangwa chose to relate the story in English and I include it here for comparative purposes:

| Bisa Storytelling, 8 by Mr. Kangwa Samson, 2005 |

| Kangwa Samson: | There lived a lion in the bush, in a cave. One day a hunter with his son went out hunting looking for animals. Unfortunately, the heavy rain rained there, so they cau…they lost their way back home. They began wandering in the bush, looking for a shelter. But as they were going, they found a cave, where the lion was. So, they entered that place and found the lion there. So the lion was very happy, thinking that they have got meat to eat now, eh? Because they were starving by hunger. And the lion demanded to eat the…? Men, the son and father. Lucky enough there was a…a small rat, known as mususungila, with a long nose. And that, eh, rat was very kind to human beings. So the lion demanded to…wanted to eat the men. But that small rat was brave. It spoke loud words, saying, “Oh, you people, don’t be afraid. If the lion eats you, I’m going to eat him also.” |

| So, the family of the lion was afraid. The lion made a plan and ordered the first son to go out and bring some firewood. And he told him that, “If you are stupid, come back. But if you are clever, don’t come back.” So the son was aware, he knew what his father meant. When he went out, he never turned back. And the second one. And the third was the wah… wife. And the last one was the real, “he” lion, the male one. They left the place. The man and his son were left alone, safe. | |

| Robert Cancel: | Because of the mouse. |

| KS: | Yeah, because of that small rat. |

This version of the narrative is certainly better developed when it comes to understanding how the lions were driven away. It also focuses specifically on the small rat, mususungila, which saved the humans. While not specified in Kangwa’s discourse, similar versions of this tale specify that the smaller animal, in this case the rat, was hidden from sight and used a fearsome voice to address the lions. An audience would fill in these details from experience if they were not provided literally in the performance. As is the case in Mr. Mwampatisha’s version, a main point is how bravado and trickery can at times overcome larger, more deadly adversaries. Moreover, this is a good example of how narratives can be shaped and reshaped depending on the intentions and focus of performers.